SHARE THIS ARTICLE

Out of Sight, Out of Mind: An Analysis of Family Mass Murder Offenders in the US, 2006-2017

1Department of Sociology, University of Central Florida

https://doi.org/10.53076/JMVR82831 | Full Citation

Volume: 1, Issue: 1, Page(s): 25-43

Article History: Received June 1, 2021 | Accepted January 21, 2022 | Published Online February 21, 2022

ABSTRACT

In recent years, media attention has increasingly focused on sensationalized forms of mass murder across the United States, thereby diverting attention on the most frequent typology of mass murder events: family mass murders. The current study addresses limitations within this body of work and provides an analysis of demographic and case characteristics associated with distinct family mass murder offender types. The current study utilizes the USA Today database, Behind the Bloodshed, and public news articles to assess 163 family mass murder incidents that occurred from 2006 to 2017. Using this database, which defines mass murder as the killing of four or more victims excluding the offender, there were an average of 14 family mass murders annually, most often committed by a current or former intimate male partner using a firearm as the weapon of choice. Additional case characteristics were examined and revealed significant differences based on the gender of the offender as well as by victim-offender relationship type. Recommendations for future research include examining the impact of gun violence prevention responses in domestic violence cases and providing a comparative study of two and three victim counts to better inform law, policy, and the public about what is often hidden away as a private family matter.

KEYWORDS

family mass murder, family killings, offender/victim relationship, mass murder, familial homicides, familicides

Mass murder, defined as four or more victims killed excluding the offender, perpetrated by one or multiple offenders within a single event (Duwe, 2000, 2004, 2007; FBI, 2005; Fox & Levin, 1998, 2015), is an extremely rare form of violence, occupying less than 1% of all U.S. homicides (Fridel, 2021; Krouse & Richardson, 2015; Levin & Fox, 1996). Yet in recent years, public mass murder incidents have gained extensive attention within large-scale news reports and in scholarly literature (Croitoru et al., 2020; Duwe, 2007; Petee et al., 1997). Though coverage on public mass murder events is important, extensive coverage on select mass murders excludes discussions of the most common typology of mass killings.

A persistent finding in research suggests that over 50% of mass murder incidents lie within the familial unit (Bowers et al., 2010; Dietz, 1986; Duwe, 2000; 2004; 2007; Fox & Levin, 1998; Fridel, 2021; Levin & Fox, 1996; Petee et al., 1997; Taylor, 2018; Zeoli & Paruk, 2020). In one of the earliest attempts to create distinct typologies of mass murder incidents, Dietz (1986) introduced the term family annihilation within the psychiatric literature. These were cases where the entire nuclear family was killed by one or two other family members. The family annihilator, otherwise referred to here as family mass murderer, was identified as the male head of household who killed at least four family members within a short time and at one location (Fox & Levin, 1998; Levin & Fox, 1996; Ressler et al., 1988). Despite an increase in attention to public mass murder events, there is a surprising dearth of research examining the most common type of these events: family mass murders (FMM).

Research on FMM incidents generally appears as a byproduct within studies focusing on broader multiple-victim homicide trends (Bowers et al., 2010; Duwe, 2007; Fox & Levin, 1994; Karlsson et al., 2021; Liem & Reichelmann, 2014) and are limited to descriptive statistics (Fegadel & Heide, 2017; Liem & Reichelmann, 2014). Although the mass murder literature in general has grown in scope by beginning to examine differences among specific mass murder types (Duwe, 2016; Petee et al., 1997; Siegel et al., 2020), there remains a dearth of literature that examines possible heterogeneity among FMM incidents. As such, it is currently unknown if, and to what extent, offender, victim, and incident characteristics differ among FMM offender types.

To advance research on mass murder, the current study quantitatively analyzes FMM1 event characteristics. Specifically, we searched for differences among offender types by examining if family mass murder case characteristics are significantly different across gender and victim-offender relationship. To meet this aim, data from USA Today’s Behind the Bloodsheddataset were utilized to gather information on 163 cases of family mass killing incidents from 2006 to 2017. Each case was then matched with news articles through Nexis Uni and Google to obtain a more detailed overview of the offenders, victims, and event characteristics. The results from the present study add to familial and mass murder literature by providing a quantitative analysis of family mass murder types beyond descriptive approaches.

Literature Review

Past Research on Mass Murder

Most research on mass murder has limited the methodological approach to descriptive case summaries with small sample sizes due to the rarity of these type of events. As such, mass murder offender typologies that have been identified by early scholars (see Fox & Levin, 1994; Holmes & Holmes, 1994; Levin & Fox, 1985; 1996; Petee et al., 1997) have seldom been empirically assessed in research, with the exception of a small number of recent studies (Fridel, 2021; Taylor, 2018). In one multivariate analysis comparing family, public, and felony mass murder events using the USA Today database, defined by incidents including 4 or more victims, Fridel (2021) found a number of significant differences across offender, victim, and incident characteristics. Fridel’s (2021) analyses suggest that incidents involving a history of domestic violence, romantic and familial difficulty, a greater number of child victims, occurring in the South, and the offender dying by suicide are more likely to be associated with a family mass murder than a felony mass murder. Additionally, Fridel’s (2021) findings suggest that family mass murder victims are more likely to be younger in age and of the same race as their victims (children or family members) when compared to both public and felony mass murders. The most significant differentiating factor between family, public, and felony mass murders were the type of victims involved.

In a separate study incorporating a multivariate analysis to examine mass murder incidents, Taylor (2018) examined possible differences in victim, offender, and incident characteristics based on an offender’s motivation to commit mass violence. Similar to Fridel’s (2021) results, Taylor (2018) found that offenders motivated by a relationship issue were more likely to kill a family member, die by suicide following the event, and be older in age than other mass murder offender types. Furthermore, her findings identified that relationship issues were present in over 40% of all mass murder cases and among these cases, a firearm was most often the lethal weapon of choice.

With research showing that gun availability substantially increases lethality in domestic violence situations (Campbell et al., 2003), scholars have begun to examine the potential link between domestic violence perpetration, firearm access, and mass murder. In an analysis of 89 offenders of mass shootings from 2014 to 2017, Zeoli and Paruk (2020) found about 30% of offenders had a suspected domestic violence history and 61% of these offenders, or 18.3% of the total, had come in contact with the criminal justice system for domestic violence. Among these individuals, only six offenders were eventually convicted of domestic violence-related charges. However, despite a conviction and qualifying for firearm restrictions, these offenders were still able to obtain a lethal weapon and execute mass killings.

In subsequent research examining 128 mass shootings from 2014 to 2019, Geller and colleagues (2021) found that about 68% of mass shootings were domestic violence related or the offender had a known history of domestic violence, and that these types of mass shootings resulted in a greater total of fatal and non-fatal victims (582 total victims) than non-domestic violence related incidents (352 total victims; see Geller et al., 2021). From these findings, some scholars have suggested that implementing stricter gun restriction policies against individuals with a domestic violence restraining order or a conviction of domestic violence could be one way to potentially lessen the opportunity of committing acts of mass violence (Geller et al., 2021; Taylor, 2018; Zeoli & Paruk, 2020). Others have similarly noted that individuals with personalities more likely to accept aggression behaviors as an appropriate solution to stress are more likely to also have a history of convictions for violent offenses, including intimate partner abuse (Peterson & Densley, 2019; Silver et al., 2018) and lethal forms of violence (Huff-Corzine & Corzine, 2020; Madfis, 2014).

Family Mass Murder

Literature on FMM is often included within more generalized research on mass murder as well as within more specific research analyses oriented on defining categories of multiple victim family homicides (e.g., Bowers, et al., 2010; Delisi & Scherer, 2006; Duwe, 2007; Karlsson et al., 2021; Liem & Koenraadt, 2008; Liem & Reichelmann, 2014; Liem et al., 2013). An important distinction between mass murder and the different types of multiple victim family homicides is that the former includes a broad definition of victims not limited to a specific type and includes cases with four or more victims. The latter employs categorical methods to analyze distinct types of multiple family homicides such as familicide (e.g., the killing of a spouse and one or more children), parricide (e.g., the killing of one’s parents), and siblicide (e.g., the killing of one’s siblings), and may include cases with one or more victims. Current mass murder literature, however, limits thorough discussions of possible heterogeneity among family mass murder instances as studies most often only examine how FMM cases are different from other types of mass murder (Dietz, 1986; Duwe, 2007; Fridel, 2021; Taylor, 2018). As such, studies examining multiple victim family homicides are useful to gain a more comprehensive understanding of specific offender, victim, and case characteristics. Notably, not all multiple victim family homicides fit the commonly accepted definition of mass murder events (4+ victims). Though recent work has suggested including multiple victim family homicide cases with 2+ or 3+ victims may offer additional insight to further understand acts of lethal violence in the family unit (Huff-Corzine & Corzine, 2020).

Cases involving the killing of multiple family members are often perpetrated by the husband or male intimate partner (Liem et al., 2013). The earliest attempt to further understand this phenomenon was completed by Frazier (1975), who identified two distinguishing motivators leading to the event as “murder by proxy” and “suicide by proxy.” “Murder by proxy” includes offenders who are motivated by anger and revenge aimed at their intimate partner following a threat of or actual withdrawal or estrangement (Websdale, 2010). In this scenario, children may also be killed because the offender sees them as an extension of the intimate partner (Liem & Reichelmann, 2014; Sillito & Salari, 2011; Wilson et al, 1995). Although the children are not regarded as the primary object of aggression, they are seen to be equally responsible for the offender’s feelings of betrayal caused by the intimate partner (Dietz, 1986; Fridel, 2021; Fox & Levin, 2011, Liem & Koenraadt, 2008; Liem & Reichelmann, 2014). Websdale (2010) further described these violent men as “livid coercive” because these offenders act out on profound feelings of anger and shame.

“Suicide by proxy” describes an offender who commits the murderous act to “protect” his family from the fate that would ensue without his financial support (Frazier, 1975; Websdale, 2010). These cases often involve offenders who have recently lost a job, face continuous unemployment, or increasing amounts of debt (Ewing, 1997; Fox & Levin, 2011; Liem & Reichelmann, 2014; Scheinin et al., 2011). Offenders most commonly view themselves as the provider and central figure of the family. Thus, when their ability to provide for their family is threatened, they may become suicidal and kill their family unit because they are seen as extension of themselves, in order to save the family from a life without the offender (Liem et al., 2013; Websdale, 2010; Wilson et al., 1995). Websdale (2010) classified this type of familicide offender as “civil reputable” and one who frequently dies by suicide following the event (Liem et al., 2013). Both distinctive familicidal offenders share a motivation marked by a sense of loss of control (Ewing, 1997; Liem & Koenraadt, 2008; Wilson et al., 1995).

Less frequent forms of multiple victim family homicides include a combination of parricides, the killing of one or more parents, and siblicides, the killing of one or more siblings. Current literature on these rare phenomena is mainly limited to case studies and descriptive statistics to explain offender, victim, and event characteristics. Findings show that most parricides and siblicides are committed by male offenders (Heide, 2013; Heide & Frei, 2010; Liem & Reichelmann, 2014; Marleau et al., 2006; Peck & Heide, 2012). In a recent study analyzing multiple family homicides, Liem and Reichelmann (2014) identified an extended parricide typology that involved cases of offenders killing their parents and siblings. They found that, similar to previous literature, most offenders were male, white, and did not typically die by suicide after the event. Compared to the other typologies identified in their study, these cases were the least likely to be premeditated and most often the perpetrator’s problems were not primarily related to the victims. The source of aggression stemmed from outside circumstances, such as intimate partner problems, unemployment, or drug/alcohol problems for which parents may be seen as partially responsible. Siblings became fatal victims as they were seen as extensions of the parents or simply witnesses that needed to be removed (Liem & Reichelmann, 2014).

To summarize, what is currently known about FMM offenders is that these instances overwhelmingly involve male perpetrators (Dietz, 1986; Duwe, 2000; 2007; Fegadel & Heide, 2017; Fox & Levin, 2011; Fridel, 2021; Liem et al., 2013), currently or formerly in a romantic relationship with at least one of the victims (Fox & Levin, 2011; Fridel, 2021; Liem et al., 2013), where firearms are frequently the weapon of choice (Fridel, 2021; Taylor, 2018), and many mass murder offenders have a recorded history of domestic violence (Fox & Levin, 2011; Fridel, 2021; Zeoli & Paruk, 2020). Additionally, among mass murder offenders with a recorded history of domestic violence, they are often not successfully restricted from acquiring firearms (Zeoli & Paruk, 2020) and involve greater fatal victim counts compared to mass murder offenders without a history of domestic violence (Geller et al., 2021).

Current Study

Previous literature on mass murder has primarily focused on the most sensationalized typologies (i.e., public mass murder) and research on multiple family homicides is generally limited to a small sample of case studies aimed to further understand only distinct subsets of familicide. Although recent scholars have begun to apply quantitative approaches beyond descriptive statistics to examine significant difference between unique types of mass murder incidents (Fridel, 2021; Taylor, 2018; Zeoli & Paruk, 2020), no studies to date have exclusively assessed the most frequent typology of mass murders. Consequently, there is an important gap in the literature that has yet to closely examine FMM cases to identify possible heterogeneity of victim, offender, and incident characteristics across offender types. As such, using the USA Today dataset, the purpose of the current study is to begin addressing this gap in literature by examining 163 U.S. family mass murder cases from 2006-2017 to assess significant differences by offender gender and victim-offender relationship.

Methods

To examine family mass murder incidents, the present study utilizes the open-access mass murder incident data from USA Today’s Behind the Bloodshed database. Based on the availability of data presented within this data source, the time period for the current study was limited to cases that occurred from 2006 to 2017 (see Overberg et al., 2016). The USA Today dataset is an interactive report that has been a preferred source by some scholars of mass murder events in recent research (Fridel, 2021; Taylor, 2018) as it overcomes known data reporting limitations of multiple victim homicide cases within the FBI’s Supplementary Homicide Report (SHR) database (see Fox & Pierre, 1996; Overberg et al., 2016). Compiled by researchers, this dataset was created through a corroborated process involving verification among the FBI’s SHR, local police records, and news media reports. Mass murder cases in the USA Today dataset were defined as a mass killing of 4 or more victims, excluding the offender, in a single event. Events may have occurred throughout hours, days, or more as long as there was no definite cooling off period. For each case, USA Today used information on the social and familial distance between offender(s) and victims to separate cases into four distinct mass murder categories: family killings, public killings, felony killings, and other. For the present study, only cases documented as family killings were collected to confirm the validity of the information of each FMM incident.

After each case listed under family killings was collected from the USA Today report, similar to previous research (Liem & Reichelmann, 2014; Liem et al., 2013; Petee et al., 1997; Taylor, 2018), Nexis Uni was utilized to find more information on the case. Specifically, data were collected to document the age of the primary offender, accomplice(s) present, victim information, the location of the event, the weapon(s) used, whether the offender died by suicide, and the motivation or trigger for the mass murder event. Together with the location, a range of a week from the date detailed on the USA Today report was first used to find each case in the Nexis Uni database. If no articles were found or there were over 50 results from the search, the articles were further filtered by keywords, such as “family,” “murder,” “killings,” or the perpetrator’s last name if that information was available on the USA Today report. If, after this approach was complete, no article was located through Nexis Uni, Google was used to identify a news source that offered more details about the case (Liem & Reichelmann, 2014).

Inclusion Criteria

We define family mass murder as any event where four or more victims are murdered, not including the offender, in one or more locations in close proximity to each other, without a cooling off period, where a majority of the victims were related to each other and have an intimate or familial relationship with the offender. Cases were excluded if there was no familial relationship between the offender and the victims, even if all of the victims were related to one another.2

Of the 185 cases originally documented under family killings in the USA Today report, twelve cases were excluded from the study because they did not fit the definition of family mass murder (i.e., the killings occurred between cooling off periods, there were less than three victims, or there was no familial relationship between offender and a majority of the victims). An additional ten cases were removed because the offender was unknown. This left a total of 163 family mass murder cases with 163 primary offenders, 397 adult victims, and 361 victims under the age of 18.

Variables

Data were collected to obtain a comprehensive look at family mass murder incidents from 2006 to 2017 based on event characteristics, offender/victim characteristics, and motivations. The event characteristics of each case were documented by the year, the month, and the state where the family mass murder occurred. Following Fox and Levin’s (1998) structure of situational characteristics, cases were further broken down to the number of incidents that occurred in each Census region of the United States. The incident locations were grouped into three categories: residential setting, multiple locations, and public settings. Additionally, information on the weapon used for the killings was gathered and categorized by gun, other close contact weapon (e.g., knife, blunt force object), multiple methods (e.g., gun and fire, gun and knife), arson, and other/unknown if the method of killing did not fit into any of these categories or no information could be found.

Offender and victim characteristics collected for the current study included offender type, the age of the offender, offender gender, the number of victims per incident, the number of minor victims per incident, whether the offender died by suicide, and whether the offender had an accomplice present. Of the 163 cases included in the study, offenders were grouped into four distinct types based on their relationship to the victims: current intimate spouse or partner, former intimate spouse or partner, direct family member, and distant family member. Cases were grouped under current intimate spouse or partner if at least one of the victims was currently married or in a relationship with the offender and the other victims were related to each other and/or to the offender in some way. The former intimate spouse or partner category included cases where at least one of the victims was once in a relationship with the offender but was estranged at the time of the mass murder incident. The remaining victims were either related to the offender or the former intimate partner. Offenders grouped under direct and distant family members included offenders who did not kill anyone they were or had been involved with in a romantic relationship with. Instead, FMM direct family member offenders only killed individuals within their immediate family unit, including parents, stepparents, siblings, and children, whereas FMM distant family member offenders killed individuals within their extended familial unit, including grandparents, aunts, and cousins.

As discussed above, there are several ways that prior research has categorized motives and triggers of offenders that commit multiple murders. The current study uses Taylor’s (2018) categories that build upon Petee et al.’s (1997) classifications of offender motivations. Although there were a handful of cases where no information could be found from our data sources on the offender’s motivation, most of the cases were categorized under one or more of the following: mental illness, financial problems, emotional triggers, and relationship issues. The mental illness of an offender was documented using explicit statements found in news sources made by law enforcement, family, or friends about specific mental health issues the offender had exhibited or was previously diagnosed with (Taylor, 2018). Financial problems were determined by information included in news sources that indicated that the offender was going through a financial hardship at the time of the event and was perceived to be one of the leading motivations for the killings. Emotional triggers were grouped by events that were motivated by a loss of a job or a documented dispute shortly before the mass murder incident. Relationship issues included cases where the offender experienced a recent loss of a relationship, had engaged in a fight with their current or former intimate spouse or partner, and/or had a history of familial disorder, or domestic violence accusations illustrated through statements by the offender or victim’s family.

Analytic Strategy

First, descriptive statistics were computed to examine the total number of family mass murders that occurred between 2006 to 2017 across all of our independent variables (Table 1). Next, to differentiate family mass murder cases across the offender’s gender and each of the four offender types, we conducted a series of bivariate analyses. Chi-square (χ2) tests were conducted for independent variables measured at the ordinal or nominal level and ANOVAs were conducted for independent variables measured at the interval/ratio level of measurement. Fisher’s exact tests were utilized when low expected counts were observed in bivariate chi-square analyses. Finally, to further examine if there are unique differences among family mass murder incidents across offender type, a multinomial logistic regression was performed. Considering that there were too few cases in the distant family member offender category, our dependent variable (FMM offender types) for the multivariate analysis was recoded to measure three distinct offender groups: current intimate partner, former intimate, and non-intimate, which combined the direct and distant family offender groups. Findings from the multinomial logistic regression will be used to determine relative risk ratios to understand which, and to what extent, victim, offender, and incident characteristics can predict the type of family mass murder offender over another. Unfortunately, due to the small sample size of female offenders, differences of family mass murder incidents across gender were not able to be analyzed. Given the exploratory nature of this study and the lack of statistical power as a result of the small sample size of FMM cases, coefficients with p ≤ 0.10 are reported as significant and discussed.

Results

Demographic and Case Characteristics

Descriptive statistics for case characteristics of the entire sample are displayed in Table 1 (column 1). From 2006 to 2017, there were an average of 14 FMMs annually, with a range of 8 incidents that occurred in 2012 and 2013 to 20 incidents in 2009. Across the 12-year span, the most common months that these incidents occurred in were April (21 incidents) and August (18 incidents). Almost half of the FMM incidents occurred in the Southern region of the U.S. (48%) and the fewest number of incidents occurred in the Northeast (7%). Furthermore, most of the cases of FMM occurred inside a residential setting (83%). In a majority of cases, the offenders used a gun as their weapon of choice (67%), followed by other close contact objects (16%) or multiple methods of killings across victim types (13%).

The majority of cases involved offenders who were current or former intimate partners (39% and 26%, respectively), by marriage or by relationship, with at least one of the victims. Direct family members were involved in 27% of the family murder cases, while distant family members accounted for 8% of the cases. Almost all offenders were male (92%) with an average age of 35. A little less than half of the FMM cases were characterized by the offender dying by suicide following the incident (44%), and only a small percentage of the cases involved the offender acting with an accomplice (5%).

FMM offenders varied in the type and number of possible motivating factors preceding the event. The average number of motivations recorded per FMM incident were 1.2. The most common motivation for offenders stemmed from relationship issues from a current or former intimate partner, with 62% of the cases falling into this category. This included family units that experienced a long history of familial disorder, those cases with associated statements of domestic violence, as well as those reported to have experienced a recent separation between the offender and one of the victims. Reports of mental illness experienced by the offender were identified as one of the motivational factors for nearly a quarter of FMM incidents (23%). Within this category, some offenders claimed that committing these acts were “a part of their destiny,” were knowingly suicidal, or had been previously diagnosed with bipolar disorder or schizophrenia. Emotional triggers, such as recent job loss or a recent prior dispute, accounted for 19% of the offender’s primary motivating factor in the cases. Finally, financial hardship was identified in 17% of the family mass murder incidents.

Bivariate Findings

The first set of bivariate analyses were conducted to examine the differences between FMM cases involving male and female offenders (Table 1, columns 2 and 3). The bivariate tests revealed significant gender differences in offender type and the likelihood of a case characterized by mental illness of the offender. To reiterate, reports of offender mental illness were captured through explicit statements found in new reports that identified specific symptoms of mental illness exhibited by the offender, irrespective of a formal mental illness diagnosis. The adjusted residuals revealed that there were significantly (χ2 = 7.66, p < 0.05) more cases of female offenders that were immediate family members (61%) than expected, and there were significantly fewer cases of male offenders who were direct family members (24%) than expected if gender and offender types were independent of each other. In other words, family mass murders committed by female offenders did not commonly involve romantic partners (current or former) as murder victims, whereas family mass murders committed by males overwhelmingly did. Cases with female offenders were significantly (χ2 = 9.15, p < 0.01) more likely to include reports regarding mental illnesses (64%) than expected compared to cases with male offenders (20%).

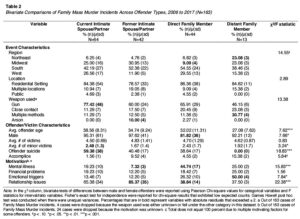

Next, bivariate analyses were conducted to assess the differences among cases based on the four offender types (Table 2). Findings suggest FMM cases with offenders under the direct family member category were less likely to occur in the Midwest (9%) than expected and cases with offenders under the distant family member category were more likely to occur in the Northeast (23%) than expected (χ2 = 14.55, p < .10). Recorded cases where the offender was categorized as a former intimate partner had the highest percentage of arson related killings (10%) as the primary method of murder. Cases with offenders categorized as current intimate partners were more often than any other category to have been perpetrated with a firearm (77%). Finally, cases where a distant family member had committed the mass murder were more likely than expected to involve multiple methods (31%) to carry out the incident (χ2 = 13.38, p < .10).

Significant results also revealed meaningful differences in age, gender, number of minor victims, suicide, and motivational factors across FMM cases based on the four offender types. Current and former intimate partners tended to be older than other offender categories, with the average ages of 39 and 35 years, respectively (χ2 = 7.62, p < .001). Direct family member offenders were more likely to be female compared to other offender types (18%; χ2 = 7.66, p < .05). Cases with offenders that were distant family members exhibited the youngest average age at 27. Cases with current intimate partner offenders were more likely to involve the killing of more victims under the age of 18 years (2.48; χ2 = 3.24, p < .05) and die by suicide following the family mass murder incident (59%; χ2 = 18.83, p < .001) compared to the other offender type cases. Interestingly, none of the cases of distant family member offenders involved suicide following the incident.

Excluding financial problems, motivations exhibited statistically significant differences in offender types. Comparisons and analysis of adjusted residuals revealed cases with former intimate partner offenders were less likely to have public reports of mental illness (7%) than expected, whereas cases with direct family member offenders were more likely to have reports of mental illness (45%) than expected (χ2 = 15.83, p < .001). Cases with offenders under the distant family member category were more likely than expected to be motivated by emotional triggers (50%; χ2 = 7.84, p < .05). Finally, it was found that cases with former intimate partner offenders were more often characterized by relationship issues (85%) as the leading motivational factor of the family mass murder incident, whereas relationship issues were less likely than expected a motivating factor for cases of direct family member offenders (39%; χ2 = 7.66, p < .001).

Multivariate Findings

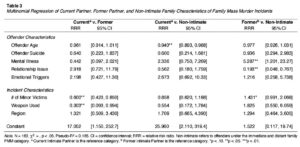

Multinomial logistic regression was performed in order to examine the effect of victim, offender, and incident characteristics on the probability of a family mass murder involving a current intimate offender, former intimate offender, or a non-intimate offender (Table 3). The relative risk ratios will be interpreted to understand which characteristics are associated with the relative risk of a FMM incident involving a specific offender category relative to the reference group. Current intimate partner FMM offender was set as the reference group for the first two comparisons in Table 3 (Current intimate partner offender [reference] vs. Former intimate partner offender; Current intimate partner [reference] vs. non-intimate partner). Former intimate offender was set as the reference group for the last comparison (Former intimate partner [reference] vs. non-intimate partner). Significant variables with relative risk ratios above one indicate that the FMM incident is more likely to be associated with the comparison category of FMM offenders, while significant relative risk ratios below one suggests that the FMM incident is more likely to be associated with the reference category of FMM offenders.

Current intimate partner FMM offenders vs. Former intimate partner FMM offenders

Two significant outcomes emerged when examining offender and incident characteristics that significantly predict the relative risk of a FMM incident involving a current intimate partner offender compared to a former intimate partner offender: the number of minor victims and offender firearm use. More specifically, for every one unit increase in the number of minor victims, the odds of the FMM incident involving a former intimate partner offender relative to a current intimate partner offender are 40% lower, controlling for all other variables. FMM incidents using a firearm have odds of involving a former intimate partner offender that are 70% lower relative to a current intimate partner offender, controlling for all other variables. In other words, FMM incidents with a greater minor victim count and FMM incidents involving a firearm are more likely to fall into the current intimate partner FMM offender category over the former intimate partner FMM offender category.

Current intimate partner offenders vs. non-intimate partner offenders

The offender age was the only significant outcome when examining offender and incident characteristics that significantly predict the relative risk of a FMM incident involving a current intimate partner offender compared to a non-intimate partner offender. For every one unit increase in the offender’s age, the odds of the FMM incident involving a non-intimate partner relative to a current intimate partner offender are 6% lower, controlling for all other variables. Put differently, as an offender’s age increases, it is more likely the FMM incident involves a current intimate partner than a non-intimate FMM offender type.

Former intimate partner offenders vs. non-intimate partner offenders

In the final multinomial logistic regression model examining offender and incident characteristics that significantly predict the relative risk of a FMM incident involving a former intimate partner offender compared to a non-intimate partner offender, three significant outcomes emerged: reported offender mental illness, relationship issues, and the number of minor victims. FMM incidents with a reported offender mental illness have odds of involving a non-intimate partner offender that are 428% higher relative to a former intimate FMM offender, controlling for all other variables. In other words, cases with non-intimate partner offenders are significantly more likely to have reports of mental illness. FMM incidents with a reported relationship issue have odds of involving a non-intimate partner offender that are 81% lower relative to a former intimate FMM offender, controlling for all other variables. Stated differently, FMM incidents with a reported relationship issue are more likely to involve former intimate FMM offenders than non-intimate partner offenders. Finally, for every one unit increase in the number of minor victims, the odds of the FMM incident involving a non-intimate partner relative to a former intimate partner are 43% higher, controlling for all other factors. This finding suggests that FMM incidents with greater minor victim counts are more likely to involve a non-intimate partner offender.

Discussion

In recent years, there has been an increase in studies conducted on mass murder with a particular focus on public mass shootings (Duwe, 2020; Petee et al., 1997; Siegel et al., 2020) as well as significant contributions to multiple victim family homicide literature (Bowers et al., 2010; Karlsson et al., 2021; Liem & Reichelmann, 2014). Yet, there are limited studies that have analyzed characteristics of the largest aggregate of mass murder occupying over 50% of cases – incidents that occur within the family. To fill this gap in the literature, this study quantitatively analyzes 163 FMM incidents in the U.S. from 2006 to 2017 across offender types. It is important to restate that the results from this study are based on a small sample of family mass murder incidents and therefore should be interpreted with caution. Nonetheless, the findings in the current study advance mass murder research by identifying distinct case differences among family mass murder offender types and providing a structure for future multivariate approaches to study FMMs.

Similar to Fox and Levin’s (1998) early work on mass murder, most cases occurred in the Southern region of the U.S. and took place in a private residence (Fox & Levin, 1998; Fridel, 2021). Additionally, in support of previous literature, FMM offenders were most often male, older in age, and chose a firearm as their primary weapon (Duwe, 2007; Fox & Levin, 1998; Fridel, 2021; Huff-Corzine et al., 2014; Taylor, 2018). Though the mental health of an offender is commonly a dominant discussion following a mass murder, consistent with previous research (Fridel, 2021; Taylor, 2018), a little less than one fourth of our sample of FMM cases included offenders with a reported mental illness concern and a little less than half of the total sample of cases involved offenders dying by suicide (Fridel, 2021). As expected, the most common motivation among the family mass murder incidents included in this study was a relationship issue between the offender and one of the victims. To reiterate, these cases included reports of a recent loss of a relationship, a known fight between a current or former intimate partner offender and at least one of the victims, history of familial disorder, and reported past domestic violence events.

When comparing cases of male and female offenders, results from our bivariate analysis revealed statistically significant gender differences in offender type and motivation. More precisely, cases with female offenders were less likely to involve a killing of an intimate partner during the family mass murder incident and more likely to have reports of mental illness as the leading motivation, whereas cases with male offenders most often involved the killing of an intimate partner and predominantly involved reports of a relationship issue as motivation for the killing. It is important to note, however, that significant gender differences observed between FMM offenders are reported based on a small sample of women offenders. Therefore, these results should be interpreted with caution until additional studies perform similar analyses to compare FMM gender differences using a bigger sample of female offenders.

From our analysis comparing cases across four offender types (current intimate partner, former intimate partner, direct family member, and distant family member), key findings from our multivariate analyses identified statistically significant differences in the weapon used, offender age, number of minor victims, as well as motivation. Though firearms were the most common weapon used across each offender type, cases with offenders that were a current intimate partner to at least one of the victims were the most likely to use a firearm than other FMM offender types. Current intimate partner FMM offenders were also more likely to kill a greater number of minor victims when compared to former intimate partner FMM offenders and more likely to be older in age when compared to non-intimate partner FMM offenders.

Though relationship issues were the most common motivation reported in the total sample of cases, bivariate results highlight cases involving offenders under the former intimate partner category were the most likely to be characterized by relationship issues as the motivating factor for committing the mass family murder. This pattern was also identified in our multivariate model. When compared to non-intimate FMM offenders, FMM offenders who were a former intimate partner with at least one of the victims were more likely to be motivated by a relationship issue.

Policy Implications

There are several key policy implications that may be taken from our findings. Research examining the relationship between mental illness and incidents of mass violence most often suggests that there is a much weaker association than what is represented in media reports (see Skeem & Mulvey, 2020). For studies that rely on informal mental illness reports of an offender gathered through news reports, scholars have identified mental illness to be a concern with only a quarter of offenders (Duwe, 2007; Fridel, 2021; Taylor, 2018). Limited studies that have collected formal psychiatric histories found an even smaller percentage (less than 20%) of adult and juvenile offenders with documented mental disorders (Fox & Fridel, 2016; Meloy et al. 2001; Skeem & Mulvey, 2020). Though media reports immediately following a mass murder event often highlight the mental health of an offender, our results support previous work to suggest that mental health is not as prominent among offenders as publicized.

A second dominant topic to mass murder responses often involve broad gun violence prevention policies, including ineffective suggestions to enact bans on assault rifles infrequently used in most mass murder incidents (Duwe, 2007). Considering that a majority of mass murder offenders obtain their firearms legally (Fox & Fridel, 2016), recent scholars have urgently suggested it is important to consider gun violence prevention policies aimed to decrease violence overall (Duwe, 2020). More precisely, if a large impact is to be made on reducing mass murder incidents, it may be important to begin by turning more attention to state and federal level domestic violence responses. Not only were relationship issues one of the primary motivations for family mass murders in our study, but offenders of other subtypes of mass murder have also noted reported histories of domestic violence prior to the attack (Fridel, 2021; Taylor, 2018; Zeoli & Paruk, 2020).

When firearms are present in a home with a suspected domestic violence offender, or anyone likely to use violence to deal with social stressors, it not only exponentially increases the risk of homicide against their intimate partner (Campbell et al., 2003) but also elevates the risk that there will be multiple victims as well (Smucker et al., 2018). In a recent analysis (Zeoli & Paruk, 2020), scholars found that among mass shooters with mention of domestic violence histories gathered from media reports, 40% did not have any formal contact with the criminal justice system for domestic violence. This leaves 60% of mass shooters in this study to be known by law enforcement to have a history of violence. Not only is the lack of criminal justice involvement among potential domestic violence offenders congruent with larger patterns of domestic violence responses in the U.S., but this study also illuminates on a number of missed opportunities by law enforcement which could have potentially prevented lethal acts of violence (see Zeoli & Paruk, 2020). Using 2005-2015 data from the National Crime Victimization Survey (NCVS) to analyze police responses to domestic violence, findings indicated that only 39% of victimizations reported to law enforcement resulted in an arrest or charges filed (Reaves, 2017). This statistic is especially concerning given that an even smaller percentage of these cases likely resulted in a formal domestic violence conviction, actions to prevent future purchase of a firearm, or relinquishment of any firearms in an offender’s possession. As such, noncriminal responses to address potentially violent domestic violence offenders are particularly crucial. Noncriminal responses to domestic violence include domestic violence restraining order (DVRO) firearm restrictions, extreme risk protection orders (ERPOs), and firearm relinquishing polices. In recent studies, authors have found that states with laws that prohibit individuals with a domestic violence-related restraining order from possessing firearms and also require the relinquishment of firearms from the individuals’ home are associated with lower state-level intimate partner homicide rates (Diez et al., 2017; Vigdor & Mercy, 2006; Zeoli & Paruk, 2020; Zeoli & Webster, 2010; Zeoli et al., 2017).

To increase the impact of current policies against potentially violent offenders, there must first be an effort encouraging families of domestic violence to report acts of violence to the police through assurance that cooperation in this process would be positive and end with a just outcome (Zeoli & Paruk, 2020). This may arguably be the biggest obstacle to overcome as research notes there are many barriers that discourage reporting of domestic disputes, such as victim fear of retaliation and discrimination (Campbell et al., 2003; Diez et al., 2017; National Domestic Violence Hotline, 2015). These barriers are especially true for minority communities. Despite higher rates of domestic violence against racial and ethnic minority women compared to White women, Black women are not only are they less likely to report abuse to law enforcement, but domestic violence offenders are less likely to be arrested when cases involve Black victims (see McCormack & Hirschel, 2021). Future research should continue to examine not only reasons why families of domestic violence do not report to the police, but also their understanding of the reporting process and awareness of life-saving firearm restriction policies against potentially violent offenders. Furthermore, there needs to be a push to adopt more effective, uniform procedures to prevent individuals with a domestic violence restraining order against them and offenders convicted of domestic violence from possessing a firearm. This includes mandatory reporting to a national firearm purchasing database as well as non-discretionary court mandated policies to relinquish firearms from the residence of perpetrators of domestic violence (Zeoli & Paruk, 2020).

Limitations

With every study there are limitations, and this study is no exception. First, we did not cross-reference cases included in this study to the FBI’s supplementary homicide report (SHR) due to known limitations of how multiple victim homicides cases are documented (Fox & Pierre, 1996; Overberg et al., 2016). However, it may be useful for future studies to cross-reference family mass murder incidents to more official data sources, such as SHR or the National Incident Based Reporting System (NIBRS; see Huff-Corzine & Corzine, 2020; Szalewski, 2020). By doing this, researchers may collect more comprehensive demographic information that may be missing from media sources. Second, while media often contains more detailed information than official data sources of mass murder incidents (Duwe, 2007; Liem & Reichelmann, 2014; Petee et al., 1997; Taylor, 2018), missing information or inaccuracies of case details gathered by media reports is possible. Also, as a result of relying solely on news media sources, the race of offender(s) and victims were not taken into account to avoid false assumptions of the racial identity of any individual based upon incomplete information provided by news reports. Lastly, results from the current study are based on a very small count of female offenders (N = 13) and a small count of FMM offender types. As such, our findings are not generalizable to FMM incidents outside of the scope of this study.

Future Research

Due to the lack of research on family mass murder incidents, there are several suggestions for future scholars to add to the literature on this topic. Future research should continue to examine case details of family mass murder incidents by collecting additional data on more specific motivations. For instance, similar to Liem and Reichelmann’s (2014) study of patterns of multiple family homicide, it would be beneficial to assess relationship issues into more detailed motivation categories such as past domestic violence convictions, presence of a restraining order, or child custody disputes. Moreover, though the current study analyzed mass murder incidents based on the most commonly adopted victim threshold (a minimum of four victims as defined by the FBI), future studies should also consider examining FMM cases with three or more victims. Broadening the inclusion criteria for family mass murder incidents will allow for a similar analysis to be conducted for smaller family types as well as increasing the statistical power to conduct a multivariate analysis with a bigger sample size of cases and to substantiate results from the current study. Additionally, as family mass murder represents the most extreme form of family violence, future work comparing family homicides with one fatal victim to cases with two, three, and four or more victims may reveal further insight to distinguishable characteristics of single victim family homicide vs. mass murder incidents. It is currently unknown if, and how, these different family homicide types are unique or similar to each other.

Conclusion

Our study has begun to bridge the gap in literature by providing an analysis of U.S. family mass murder cases from 2006 to 2017. Results from the current study support that there is heterogeneity within family mass murder incidents, highlighting key differences based on an offender sex and victim-offender relationship type. As expected, one of the leading motivations for a family mass murder attack stemmed from a relationship issue between the offender and at least one of the victims. The current study highlights the importance for future scholars to begin paying more attention to family mass murders – the largest aggregate of mass murder events. In the end, efforts need to focus on improving strategies to prevent potentially violent offenders, especially in domestic settings.

NOTES

- In this study, family mass murder is defined as any event where four or more victims are murdered not including the offender, in one or more locations in close proximity to each other, without a cooling off period, where a majority of the victims were related to each other through a relationship to the offender.

- For example, on May 14th, 2015, a mass murder incident occurred involving an offender that was a former employee of one of the victims. In addition to killing a former employer, the offender also killed his former employer’s wife, son, and housekeeper after extorting the family of $40,000 (Brown et al., 2015). This incident was excluded from our analysis because although the majority of the victims were connected by a familial relationship, the offender is not a family member by blood or an intimate relationship with any of the victims.

- Due to the small sample size, variable selection was carefully considered. Variables that showed a significant bivariate relationship with the offender relationship, with the exception of offender’s gender, were included in the multivariate model. Offender’s gender was unable to be included in the final model because the majority of cases involved male offenders.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflicts of interest were reported by the authors.

REFERENCES

Bowers, T. G., Holmes, E. S., & Rhom, A. (2010). The nature of mass murder and autogenic massacre. Journal of Police Criminal Psychology, 25(2), 59-66. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11896-009-9059-6

Campbell, J. C., Webster, D. W., Koziol-McLain, J., Block, C., Campbell, D., Curry, M. A., Gary, F., Glass, N., McFarlane, J., Sachs, C., Sharps, P., Ulrich, Y., Wilt, S. A., Manganello., J., Xu, X., Schollenberger, J., Frye, V., & Laughon, K. (2003). Risk factors for femicide in abusive relationships: Results from a multisite case control study. American Journal of Public Health, 93(7), 1069-1097. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.93.7.1089

Croitoru, A., Kien, S., Mahabir, R., Radzikowski, J., Crooks, A., Schuchard, R., Begay, T., Lee, A., Bettios, A., & Stefanidis, A. (2020). Responses to mass shooting events: The interplay between the media and the public. Criminology & Public Policy, 19(1), 335-360. https://doi.org/10.1111/1745-9133.12486

Delisi, M., & Scherer, A. M. (2006). Multiple homicide offenders: offense characteristics, Social correlates, and criminal careers. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 33(3), 367-391. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093854806286193

Dietz, P. E. (1986). Mass, serial, and sensational homicides. Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine, 62(5), 477-491. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1629267/pdf/bullnyacadmed00051-0111.pdf

Diez, C., Kurland, R. P., Rothman, E. F., Bair-Merritt, M., Fleegler, E., Xuan, Z., Galea, S., Ross, C. S., Kalesan, B., Goss, K. A., & Siegel, M. (2017). State intimate partner violence-related firearm laws and intimate partner homicide rates in the United States, 1991 to 2015. Annals of Internal Medicine, 167(8), 536-543. https://doi.org/10.7326/M16-2849

Duwe, G. (2000). Body-count journalism: The presentation of mass murder in the news media. Homicide Studies, 4(4), 364-399. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088767900004004004

Duwe, G. (2004). The patterns and prevalence of mass murder in twentieth-century America. Justice Quarterly, 21(4), 729-761. https://doi.org/10.1080/07418820400095971

Duwe, G. (2007). Mass murder in the United States: A history. McFarland & Company.

Duwe, G. (2016). Patterns and prevalence of mass public shootings in the United States, 1915- 2013. In L. C. Wilson (Ed)., The Wiley Handbook of the Psychology of Mass Shootings (pp. 20-35). John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Duwe, G. (2020). Patterns and prevalence of lethal mass violence. Criminology & Public Policy, 19(1), 17-35. https://doi.org/10.1111/1745-9133.12478

Ewing, C. P. (1997). Fatal families. Sage.

Federal Bureau of Investigation. (2005). Serial murder: Multi-disciplinary perspectives for investigators. U.S. Department of Justice. https://www.fbi.gov/stats-services/publications/serial-murder/serial-murder-july-2008-pdf

Fegadel, A. R., & Heide, K. M. (2017). Offspring-perpetrated familicide: examining family homicides involving parents as victims. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 61(1), 6-24. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306624X15589091

Fox, J. A., & Fridel, E. E. (2016). The tenuous connections involving mass shootings, mental illness, and gun laws. Violence and Gender, 3(1), 14119. https://doi.org/10.1089/vio.2015.0054

Fox, J. A., & Levin, J. (1994). Overkill: Mass murder and serial killing exposed. Plenum Press.

Fox, J. A., & Levin, J. (1998). Multiple homicide: Patterns of serial and mass murder. Crime and Justice, 23, 407-455. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1147545

Fox, J. A., & Levin, J. (2011). Extreme killing: Understanding serial and mass murder (2nd ed.). Sage.

Fox, J. A., & Levin, J. (2015). Mass confusion concerning mass murder. The Criminologist, 40(1), 8-11. https://www.hoplofobia.info/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/Mass-Confusion-Concerning-Mass-Murder.pdf

Fox, J. A., & Pierre, G. L. (1996). Uniform Crime Reports [United States]: Supplementary Homicide Reports, 1976-1983 (ICPSR 8657). Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research. https://www.ojp.gov/pdffiles1/Digitization/107057NCJRS.pdf

Frazier, S. H. (1975). Violence and social impact. In J. C. Schoolar (Ed.), Research and the Psychiatric Patient (pp.191-200). Brunner & Mazel.

Fridel, E. E. (2021). A multivariate comparison of family, felony, and public mass murders in the United States. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 36(3–4), 1092-1118. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260517739286

Geller, L. B., Booty, M., & Crifasi, C. K. (2021). The role of domestic violence in fatal mass shootings in the United States, 2014-2019. Injury Epidemiology, 8(1), 38. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40621-021-00330-0

Heide, K. M. (2013). Understanding parricide: When sons and daughters kill parents. Oxford University Press.

Heide, K. M. & Frei, A. (2010). Matricide: A critique of the literature. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 11(1), 3-17. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838009349517

Holmes, R. M., & Holmes, S. T. (1994). Murder in America. Sage.

Huff-Corzine, L., & Corzine, J. (2020). The devil’s in the details: Measuring mass violence. Criminology & Public Policy, 19(1), 317-333. https://doi.org/10.1111/1745-9133.12482

Huff-Corzine, L., McCutcheon, J. C., Corzine, J., Jarvis, J. P., Tetzlaff-Bemiller, M. J., Weller, M., & Landon, M. (2014). Shooting for accuracy. Homicide Studies, 18(1), 105-124. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088767913512205

Karlsson, L. C., Antfolk, J., Putkonen, H., Amon, S., Guerreiro, J. D., Vogel, V. D., Flynn, S., & Weizmann-Henelius, G. (2021). Familicide: A systematic literature review. Trauma, Violence, and Abuse, 22(1), 83-98. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838018821955

Krouse, W. J., & Richardson, D. J. (2015). Mass murder with firearms: Incidents and victims, 1999-2013. Congressional Research Service.

Levin, J., & Fox, J. A. (1985). Mass murder: America’s growing menace. Plenum Press.

Levin, J., & Fox, J. A. (1996). A psycho-social analysis of mass murder. In T. O’Reilly-Fleming (Ed.), Serial and mass murder: Theory, research, and policy (pp. 55-76). Canadian Scholars’ Press.

Liem, M., & Koenraadt, F. (2008). Familicide: A comparison with spousal and child homicide by mentally disordered perpetrators. Criminal Behavior and Mental Health, 18(5), 306-318. https://doi.org/10.1002/cbm.710

Liem, M., & Reichelmann, A. (2014). Patterns of multiple family homicide. Homicide Studies, 18(1), 44-58. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088767913511460

Liem, M., Levin, J., Holland, C., & Fox, J. A. (2013). The nature and prevalence of familicide in the United States, 2000–2009. Journal of Family Violence, 28(4), 351-358. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-013-9504-2

Madfis, E. (2014). Triple entitlement and homicidal anger. Men and Masculinities, 17(1), 67-86. https://doi.org/10.1177/1097184×14523432

Marleau, J. D., Auclair, N., & Millaud, F. (2006). Comparison of factors associated with parricide in adults and adolescents. Journal of Family Violence, 21(5), 321-325. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-006-9029-z

McCormack, P. D., & Hirschel, D. (2021). Race and the likelihood of intimate partner violence arrest and dual arrest. Race and Justice, 11(4), 434-453. https://doi.org/10.1177/2153368718802352

Meloy, J. R., Hempel, A. G., Mohandie, K., Shiva, A. A., & Gray, B. T. (2001). Offender and offense characteristics of a nonrandom sample of adolescent mass murderers. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 40(6), 719-728. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-200106000-00018

National Domestic Violence Hotline. (2015). Who will help me? Domestic violence survivors speak out about law enforcement responses. https://www.thehotline.org/wp-content/uploads/media/2020/09/NDVH-2015-Law-Enforcement-Survey-Report-2.pdf

Overberg, P., Hoyer, M., Hannan, M., Upton, J., Hansen, B., & Durkin, E. (2016). Explore the data on U.S. mass killings since 2006. USA TODAY. http://www.usatoday.com/story/news/nation/2013/09/16/mass-killings-data- map/2820423/

Peck, J. H., & Heide, K. M. (2012). Juvenile involvement in fratricide and sororicide: An empirical analysis of 32 years of U.S. arrest data. Journal of Family Violence, 27(8), 749-760. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-012-9456-y

Petee, T. A., Padgett, K. G., & York, T. S. (1997). Debunking the stereotype: An examination of mass murder in public places. Homicide Studies, 1(4), 317-337. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088767997001004002

Peterson, J., & Densley, J. (2019). The Violence Project mass shooter database. The Violence Project. https://www.theviolenceproject.org

Reaves, B. A. (2017). Police response to domestic violence, 2006–2015 (NCJ 250231). Bureau of Justice Statistics. https://www.bjs.gov/index.cfm?ty=pbdetail&iid=5907

Ressler, R. K., Burgess, A. W., & Douglas, J. E. (1988). Sexual homicide: Patterns and motives. Simon and Schuster.

Scheinin, L., Rogers, C. B., & Sathyavagiswaran, L. (2011). Familicide-suicide: A cluster of 3 cases in Los Angeles County. The American Journal of Forensic Medicine and Pathology, 32(4), 327-330. https://doi.org/10.1097/PAF.0b013e31821a555a

Siegel, M., Goder-Reiser, M., Duwe, G., Rocque, M., Fox, J. A., & Fridel, E. E. (2020). The relation between state gun laws and the incidence and severity of mass public shootings in the United States, 1976–2018. Law and Human Behavior, 44(5), 347-360. https://doi.org/10.1037/lhb0000378

Sillito, C. L., & Salari, S. (2011). Child outcomes and risk factors in US homicide-suicide cases 1999–2004. Journal of Family Violence, 26(4), 285-297. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-011-9364-6

Silver, J., Simons, A., & Craun, S. (2018). A study of pre-attack behaviors of active shooters in the United States between 2000 and 2013. Federal Bureau of Investigation, U.S. Department of Justice, Washington, D.C.

Skeem, J., & Mulvey, E. (2020). What role does serious mental illness play in mass shootings, and how should we address it?. Criminology & Public Policy, 19(1), 85-108. https://doi.org/10.1111/1745-9133.12473

Smucker, S., Kerber, R. E., & Cook, P. J. (2018). Suicide and additional homicides associated with intimate partner homicide: North Carolina 2004–2013. Journal of Urban Health, 95(3), 337-343. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-018-0252-8

Szalewski, A. (2020). Family mass homicide: An investigation [Doctoral Dissertation, University of Central Florida]. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd2020/301

Taylor, M. A. (2018). A comprehensive study of mass murder precipitants and motivations of offenders. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 62(2), 427-449. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306624X16646805

Vigdor, E. R., & Mercy, J. A. (2006). Do laws restricting access to firearms by domestic violence offenders prevent intimate partner homicide? Evaluation Review, 30(3), 313-346. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193841X06287307

Websdale, N. (2010). Familicidal hearts: The emotional styles of 211 killers (Vol. 5.). Oxford University Press.

Wilson, M., Daly, M., & Daniele, A. (1995). Familicide: The killing of spouse and children. Aggressive Behavior, 21(4), 275-291. https://doi.org/10.1002/1098-2337(1995)21:4%3C275::AID-AB2480210404%3E3.0.CO;2-S

Zeoli, A. M., & Paruk, J. K. (2020). Potential to prevent mass shootings through domestic violence firearm restrictions. Criminology & Public Policy, 19(1), 129-145. https://doi.org/10.1111/1745-9133.12475

Zeoli, A. M., & Webster, D. W. (2010). Effects of domestic violence policies, alcohol taxes and police staffing levels on intimate partner homicide in large U.S. cities. Injury Prevention, 16(2), 90-95. https://doi.org/10.1136/ip.2009.024620

Zeoli, A. M., Frattaroli, S., Roskam, K., & Herrera, A. K. (2017). Removing firearms from those prohibited from possession by domestic violence restraining orders: A survey and analysis of state laws. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 20(1), 114-125. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838017692384

About the Authors

Madelyn L. Diaz is a PhD student in the Department of Sociology at the University of Central Florida, where she also received her M.A. in Applied Sociology and B.A. in Criminal Justice. Her research interests include lethal and non-lethal forms of gender-based violence, more specifically sexual victimization, post-victimization health outcomes, human trafficking, and the unequal impact of violence across marginalized communities. She has published in Crime & Delinquency, LGBT Health, and Sociation.

Kayla Toohy is a PhD candidate in the Department of Sociology at the University of Central Florida, received her B.A. and M.A. from the University of Memphis in Criminology and Criminal Justice where she also received a graduate certificate in Geographic Information Systems (GIS). Her research interests include violent crime and lethal violence, particularly regarding macro-level geospatial studies of homicide in United States cities. Toohy’s work is published in the American Journal of Criminal Justice, Homicide Studies, and Applied Geography.

Ketty Fernandez, M.A. is a PhD candidate (ABD) in the Department of Sociology at the University of Central Florida. Her research interests include violence against women, with an emphasis on domestic violence and sexual victimization among women of color, human trafficking, and racial/ethnic inequalities. Her work appears in Criminal Justice Policy Review, Sociation, and Policing: An International Journal.

Lin Huff-Corzine, PhD is a Professor in the Department of Sociology at the University of Central Florida. Her research on lethal and non-lethal violence spans three decades with work on homicide examining topics including but not limited to lynching, domestic violence, regional variations, transportation effects on lethality, human trafficking, and more recently mass murder. Dr. Huff-Corzine’s publications can be found in edited collections as well as journals such as Homicide Studies,Justice Quarterly, Violence and Victims, Social Forces, Victims and Offenders, Criminology, and Deviant Behavior.

Amy Reckdenwald, PhD is an Associate Professor in the Sociology Department at the University of Central Florida. Her research interests include violent victimization and offending; particularly as it relates to domestic violence and intimate partner homicide. Her work appears in journals such as Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, Criminology, Homicide Studies, Feminist Criminology, Journal of Criminal Justice, and Violence and Victims.

CITATION (APA 7th Edition)

Diaz, M. L., Toohy, K., Fernandez, K., Huff-Corzine, L., & Reckdenwald, A. (2022). Out of sight, out of mind: An analysis of family mass murder offenders in the US, 2006-2017. Journal of Mass Violence Research, 1(1), 25-43. https://doi.org/10.53076/JMVR82831