SHARE THIS ARTICLE

Rage, Prayers, and Partisanship: US Congressional Membership's Engagement of Twitter as a Framing Tool Following the Parkland Shooting

1School of Justice Studies, Eastern Kentucky University

2Newhouse School of Public Communications, Syracuse University

3Department of Psychology, Stetson University

Article History: Received February 17, 2023 | Accepted September 25, 2023 | Published Online November 5, 2023

ABSTRACT

Twitter is a popular social medium for members of U.S. Congress, and the platform has become focal for framing policy discussions for constituents and the media. The current study examines the corpus of N = 5,768 Congressional tweets sent on the day of and week following the 2018 Parkland shooting, over 25 percent of which (n = 1,615) were related to the shooting. Democrats were far more likely to engage Parkland as a prominent topic in their Twitter feeds. Democrats framed Parkland discussions in terms of outrage and criticism, as well as discussions of the potential causes of and (legislative) solutions to gun violence. Republicans mostly avoided Parkland discussions and political framing.

KEYWORDS

U.S. Congress, framing theory, Parkland shooting, gun control, Twitter

On February 14, 2018, a teenage gunman shot and killed 17 people and injured 14 others at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida, in what is colloquially referred to as “the Parkland shooting.”1 In response to the Parkland shooting politicians turned to various media channels and outlets, including their own social media accounts, to express grief for victims, discuss gun violence and gun control policies, and generally engage the public. Such social media engagement could be seen as a natural extension of Congressional office – engaging with constituents in an open and public space. However, this engagement can also be understood through the lens of framing theory (Goffmann, 1974), as “frames” exist as a way for politicians to quickly establish heuristics for how these issues are discussed by constituents (Conway et al., 2015) and taken up by media institutions (Shapiro & Hemphill, 2016). To this end, the current study takes a quantitative content analysis approach to analyze the frequency and qualitative content of the population of Tweets sent by members of Congress on the day of and week following the Parkland Shooting. We do this to (a) analyze the discussion frames used in those tweets and to (b) understand key Congressional variables (such as political party affiliation) that correlate with the use of some frames over others.

Literature Review

The Parkland shooting was unique and politically important because of the social significance and volume of the social movements which took place after the shooting. The Parkland shooting commanded more news coverage than any other recent school shooting both in volume and duration (Nass, 2018), with perhaps the exception of the Robb Elementary School shooting in Uvalde, Texas on May 24, 2022 in which 19 students and two teachers were killed (Osteen, 2022).2 One of the distinctive aspects of The Parkland shooting was the fact that its coverage extended beyond the normal 30-day lifespan of mass shooting coverage in the U.S. (Holody, 2020). The Parkland shooting garnered social significance in large part from survivor gun control activists. These activists engaged Florida state and federal politicians, as well as the NRA to take up legislative solutions to gun violence, such as regulations for stricter gun control. In the days after the shooting, survivors challenged politicians who offered prayers and condolences on Twitter, staged school walkouts, and even directly challenged Florida Senator Marco Rubio at a town hall meeting for his acceptance of NRA campaign contributions – much of this culminating in the March 24, 2018, nationwide “March for Our Lives” (Torres, 2018). Much of this conversation took place via Twitter (Williams et al., 2019).

Social media has influenced how politicians interact with their constituents, making it easier and faster to disseminate messages to broader audiences (Straus & Glassman, 2016). Research has identified major social media platform (Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube) usage rates of between 94 and 100% for members of the Senate and between 87 and 100% for Representatives (Straus, 2018). Congressional members use social media to gauge their constituents’ opinions and communicate their own political views and activities to the public (Congressional Management Foundation, 2011), although Golbeck, Grimes, and Rogers (2010) suggest that this usage tends “not to provide new insights into government or the legislative process or to improve transparency; rather, they are vehicles for self-promotion” (p. 1612). Similarly, the political stances adopted by most politicians tend to cluster broadly around conservative or liberal leanings, rather than being issue specific (Copenhaver et al., 2017).

One way to consider this Congressional engagement with social media is through the perspective of framing, or the “selection of some aspects of a perceived reality” (Entman, 1993, p. 52), which results in audiences paying attention to some elements of an event more than others. Framing efforts are purposeful and uniquely communicative in nature, as they are formed through the careful selection and omission of information (Entman, 1993; Gitlin, 1981), and are politically advantageous to politicians who employ such frames. Iyengar (1990) suggests that framing efforts are a crucial tool for assigning blame or responsibility for political issues. Scholarly research on mass shootings has a history of employing framing analysis to understand how media covers mass shooting events, as well as how it further influences the public’s understanding of such events. In one example, Silva (2021) found the New York Times employed four different frames in its coverage of mass shooting events from 2000 to 2016: 1) gun access, 2) mental illness, 3) violent entertainment, and 4) terrorism. In another example, Schildkraut and Muschert (2014) found that media coverage is not stagnant over time in terms of the frames it chooses to cover such events.

Congressional members and their campaigns fuel social media conversations with potential discussion. For example, Lee and Xu (2018) found that attacks and other negative tweets sent by campaigns are more likely to be engaged, while also resulting in more followers (and thus, more users to take up and promote the candidate and campaign messages). This careful crafting of discussion frames is magnified when users engage very selective and specific political ideologies while online. Hong and Kim (2016) report that politicians who take more extreme political positions tend to have more Twitter followers. Wang et al. (2017) were able to predict Twitter users as being either Donald J. Trump or Hillary Clinton followers, based on the user’s everyday tweets and shared photos. Lee et al. (2014) demonstrate that even in groups that are not politically polarized, users still amplify political frames—likely a function of confirmation bias by which individuals with strong opinions simply reinforce these opinions through continued efforts to defend their opinions (see Guerin & Innes, 1989). In all of this, as politicians use Twitter to distribute their own political messages, those messages are taken up and distributed by ardent ideologues and thus, reinforcing the discussion frames that originate from these politicians (Hemphill et al., 2013). The Parkland shooting is a particular example of how this process works, as gun-violence policy advocates drove social media engagement across both Instagram and Twitter in the wake of the shooting (Austin et al., 2020).

The Current Study

The current study involves two broad exploratory research questions. First, we are curious to understand (RQ1) What were the common frames in U.S. Congressional tweets in response to the Parkland Shooting? Following, we ask (RQ2) Did those frames vary as a function of (a) the political affiliation of the Congressional member (b) the amount of funding the Congressional member received from the NRA, or (c) the proximity of the Congressional member to Parkland, FL?

Method

The data for this project includes a complete analysis of active public U.S. Congressional Twitter accounts from the day of the Parkland shooting (February 14, 2018), to one week following the shooting (February 21, 2018). English-language tweets were gathered using Twitter’s native search function via a customizable URL below:

https://twitter.com/search?l=&q=from%3A

[Insert Twitter Handle]

%20since%3A2018-02-14%20until%3A2018-02-21&src=typd&lang=en

The complete database for this project (N = 5,768 unique tweets), as well as our coding and data analyses, are freely available online: https://osf.io/h9mev/?view_only=b7c17f1d35834e9ebd4299a2cacffb70. These tweets were analyzed using a mixed methodological approach, first by using thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006) to induce emergent themes from the data corpus (RQ1), and then using quantitative content analysis techniques (Neuendorf, 2002) to compare the frequency of those induced themes as a function of relevant independent variables (RQ2).

A total of 526 of a potential 536 (98.13%) Congress members were included in final analysis (n = 97 Senate members, n = 429 House members),3 as not all members had public Twitter accounts during our search frame. The gender breakdown of all Congress members was 114 female (21.3%) and 422 males (78.7%), and included 419 White (79.7%), 47 Black (8.9%), and Hispanic (5.5%) individuals. The average member age was 59.32 (SD = 10.80) years, with a range of 33 to 87, and they had served in Congress an average of 10.43 (SD = 9.08) years, ranging from “1” to “45.” By political party, 54.6% (n = 287) were Republicans and 45.4% (n = 239) were Democrats. By region, 185 (35.2%) were from Southern states, 94 (17.9%) from Northeastern states, 116 (22.1%) from Midwestern states, 126 (24.0%) from Western states, and 5 (1%) from other territories and regions of the U.S. with non-voting representation in US Congress. Raw NRA scores (pulled from www.votesmart.org) were translated into letter grades, with 251 (47.7%) members earning a rating of “A”, and 234 (44.5%) earning a grade of “F.” Given this bimodal distribution, we decided to break the sample into “passing” grades of “C,” “B,” and “A” (n = 278, or 53.9% of the sample), and “failing” grades of “D” and “F” (n = 238, 46.1%); 10 members did not receive an NRA score. Notably, there was a very strong correlation between political party affiliation (being a Republican coded as “1”) and both accepting NRA donations4 (r = .802, p < .001, n = 523) and receiving a passing grade from the NRA (r = .918, p < .001, n = 516) and thus, the measures are empirically isomorphic. For this reason, only political affiliation scores were retained for further analyses.

NRA grades are established by considering where a political candidate stands on the gun control issue, regardless of whether they identify politically as a Republican, Democrat, Independent, etc. The NRA reviews candidates based on a candidate’s public statements about gun control, voting record on gun control issues, and responses to the NRA-PVF or National Rifle Association-Political Victory Fund Questionnaire. Overall, the NRA grades political candidates according to how well a candidate recognizes gun control efforts as futile in crime fighting efforts, as well as infringing upon U.S. citizens’ Second Amendment rights (Votesmart, 2023). It is pertinent to note that simply receiving the grade of “A” does not automatically equate to a candidate receiving monetary support from the NRA.

Congressional members in this sample sent an average of 2.33 (SD = 4.23) tweets during the scrape period – .72 (SD = .838) on the day of the shooting, and 1.61 (SD = 3.87) on the week of the shooting. Just under 70% (n = 367) of Congressional members made at least one Parkland-related tweet. On the day of the Parkland shooting, Congressional members made 411 tweets about the event specifically (of n = 1,651 total tweets made that day, or about 25% of all Congressional tweets that day). For the entire scrape period, 1,204 tweets about Parkland were sent (about 20% of all Congressional tweets for that period).

Results

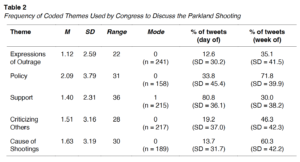

For the first research question, an emergent thematic analysis was used to uncover consistent patterns of discussion in the corpus of tweets, an inductive and qualitative analysis approach suggested by Braun & Clarke (2006). For this process, a random selection of 10% of all Twitter accounts (n = 55) was given a deep read by one author of this project, resulting in five emergent frames: expressions of outrage, policy, support, criticizing others, and causes of shootings (Table 1). These themes were independently confirmed by a different author and provide the answer to RQ1. Notably, theoretical saturation was reached within this 10% sample.

After establishing the themes above (and thus answering RQ1), the two coding authors then assigned binary codes (“0” for absence, “1” for presence) to 10% of the data corpus to prepare data for answering RQ2 (the quantitative comparison of the frequency of induced themes as a function of pre-defined variables; see Neuendorf, 2002). Coders achieved acceptable interrater reliability on each discussion frame category (calculated as Krippendorf’s a): expressions of outrage = .882, policy = .897, support = .939, criticizing others = .897, cause of shootings = .884.5 It is important to note that coding categories are not mutually exclusive, and one individual Tweet could be coded across multiple frames.

Having established the validity of these five themes, or frames, their sample-wide frequencies are reported below in Table 2 – these, based on 367 Congressional members who had at least one Parkland-related tweet. In sum there were 1,615 Congressional tweets included in the sample. All 1,615 Tweets were included in the data analysis, with results presented below in Tables 2 and 3 below.

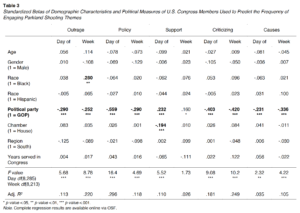

For the focal test of RQ2, the proportion of each of the five tweet categories (for both the day of the Parkland shooting and the week of the Parkland shooting) was regressed onto each of the eight independent variables above. For tweets sent on the day of the Parkland shooting, all five regression models were significant (see Table 3) and showed a clear pattern such that Democrats were more likely to demonstrate outrage, discuss policy, share criticism, and discuss causes of school shootings, while Republicans were more likely to tweet messages of support. These same patterns were replicated when examining each Parkland theme for the week following the Parkland shooting (although variance in engaging the support frame was non-significant).

Discussion

The Parkland shooting represented a critical moment in the modern political discourse that dominated U.S. newspaper headlines and social media discussions for weeks following the event. Social media was saturated with discussions about Parkland, including engagement from members of U.S. Congress who took to Twitter to share their views and perspectives. The goals of this project were to analyze Congressional engagement with Twitter on the day of and in the week following Parkland, and to both (a) identify common discussion frames within those Congressional tweets and (b) explore potential patterns associated with the use of those frames.

As presented in Table 1, five discussion frames emerged in our data: expressions of outrage, calls for policy, support for victims and first responders, criticizing others, and discussing the causes of such shootings. As might be expected, support frames were far more common in Parkland-related tweets on the day of the shooting (nearly 81% of all tweets), which can be broadly understood through the lens of rally effects, by which immediate reactions to crises tend to be more supportive than critical (Baker & Oneal, 2001). That said, political framing increased sharply in the days following the shooting—that is, there was an increase in the number of tweets expressing outrage, discussing policy, criticizing others (such as other politicians and entities), and debating the causes of school shootings.

On the day of the shooting, nearly one in four Congressional tweets focused on the Parkland shooting; in one week following the shooting, nearly one in five tweets were still discussing Parkland. Such engagement clearly highlights the importance of the shooting to members of Congress, but a closer look at the political affiliation of those members shows starkly different engagement among Democrats and Republicans. After controlling for numerous other factors, Republicans were far less likely (73% less likely) to tweet about Parkland than Democrats; when they did, Congressional Republicans tweeted their support for victims on the day of the shooting and said very little afterwards. Conversely, Democrats were far more likely to engage political frames associated with outrage, policy changes, criticizing others, and causes of shootings.

Implications

From the perspective of framing theory, both patterns align with partisan politics. In particular, for the pro-gun control Democrat platform, the official stance of the Democratic National Committee is that “[w]ith 33,000 Americans dying every year, Democrats believe that we must finally take sensible action to address gun violence” (see Democratic National Committee, 2023, para. 1). For Democrats, the Parkland Shooting seems to have served as a catalyst for engaging social media to provide discussion frames towards legislative solutions to mass shootings. Democrats’ dual engagement of emotional themes (criticism and outrage), as well as more practical themes (potential causes of and solutions to gun violence), shows an effort to push dialogue around the Parkland shooting proactively, ostensibly to reinforce the party’s larger political platform. Conversely, Republican members of Congress seemed to avoid any political elaboration related to the Parkland shooting. Republicans were far more likely to show initial support for the victims and others affected by the shooting (such as first responders), often in the form of thoughts and prayers, before turning attention away from any further discussion of the Parkland shooting. One interpretation of such a finding is that Republican members chose to disengage from any further discussion of the shooting, perhaps to either (a) reduce focus on debates and discussion of gun control not central to their national platform or (b) draw focus away to other topics (although here, our current analysis does not attempt to interpret non-Parkland related tweets, and as such, these were excluded from data collection and analysis). These findings are somewhat confirmed by a broader comparison of Tweets sent as a function of political affiliation, wherein Democrats sent nearly 100% more tweets on the day of the shooting, and nearly 400% more tweets during the week following the shooting. For Democrats, the Parkland shooting provided the opportunity to engage several different discussion frames associated with gun violence.

Limitations

There are limitations to this study which must be discussed. Twitter was the focus of this study due to its centrality in modern political campaigning as well as the public structure of the platform (Lee & Xu, 2018), but future work might consider other social platforms. Additionally, two central themes of the research highlighted in this study surround: 1) number of tweets and 2) content of tweets. First, as it pertains to the number of tweets, future research should also study how the number of tweets politicians send after a tragedy affects public support for politicians as individuals. Since most constituents never have direct interactions with their representatives, the public has limited opportunities to see their politicians at work. Do tweets affect how members of the public see their leaders and affect their perceptions of the amount and quality of the work they perform? Does this further influence public policy when the public feels satisfied about a particular politician based on the impression management of their Twitter account? Second, are there differences in how politicians respond to mass shootings since the passage of the Bipartisan Safer Communities Act? After the Uvalde shooting, Congress passed a historical bill designed to increase background checks for certain individuals wishing to purchase a firearm, increased community access to mental health services, and provided resources to make schools safer (see Executive Office of the President, 2022). In the current study there were important differences in whether and how members of Congress tweeted about the Parkland shooting. Given the bipartisan nature of the Bipartisan Safer Communities Act, which was supported by both major political parties, would similar tweeting behaviors observed in this study be seen after a mass shooting? Alternatively, would members of Congress be more akin to send similar messages after such a tragic event given that both parties adopted the Safer Communities Act?

Future work might also extend the analysis frame to a longer time-lag, which might reveal other discussion frames or the evolution of initial frames; some members of Congress (including the Republicans in this sample) might have been trying to avoid accusations of “politicizing tragedies” (Robinson, 2017) and thus, stayed silent. A particularly intriguing area for future work would be to correlate emerging discussion frames with agenda-setting effects—that is, to understand how these tweets might impact downstream media coverage and public discourse (Neuman et al., 2014). For example, Donald J. Trump’s 2016 campaign for the U.S. Presidency was successful and largely built on his ability to engage and leverage Twitter to establish issue frames (Wells et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2017), and his success is a bellwether for future campaigns.

Conclusion

Overall, this study adds to the framing theory literature on how politicians use Twitter in responding to a highly publicized school shooting. This study also adds to the broader framing literature that examines how media coverage of mass shooting events is framed. Particularly, this study furthers understanding of how politicians framed a highly politicized school shooting tragedy. Emphasized above was the fact that news media coverage of The Parkland shooting was different in terms of its salience, as measured by the extended lifespan of the event’s coverage. As such, the Parkland shooting and the social response to it, including media coverage, must be analyzed as part of a contemporary understanding of the mass shooting problem in the U.S. Furthermore, this research points to the need to study other highly publicized and politicized mass shootings and school shootings in particular, while focusing on how politicians employ frames via media in the aftermath of mass shootings.

NOTES

- We refer to the mass school shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in February, 2018 as “The Parkland shooting”, as is often colloquially done in the United States.

- In addition to traditional national media “swarming” of school shooting locations, ABC created the news series “Uvalde:365” to provide coverage across all its network programs and platforms (Osteen, 2022).

- Eight Representatives did not have Twitter accounts. Two Senators did not have Twitter accounts.

- Only four Democrats in our study had received campaign contributions from the NRA: Sanford Bishop, Henry Cuellar, Collin Peterson, and Timothy Walz. However, Bishop and Peterson had no Twitter account active during our analysis, and Cuellar made no posts about Parkland. Peterson discussed gun control concerns and victim support in his lone Parkland tweet, sent the day of the attack: https://twitter.com/RepTimWalz/status/963909358433292290.

- Complete coder training details, as well as alternative metrics of intercoder reliability, are available in our online supplement files on OSF.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflicts of interest were reported by the authors.

REFERENCES

Austin, L., Guidry, J., & Meyer, M. (2020). #GunViolence on Instagram and Twitter: Examining Social Media Advocacy in the Wake of the Parkland School Shooting. The Journal of Public Interest Communications, 4(1). https://doi.org/10.32473/jpic.v4.i1.p4

Baker, W. D., & Oneal, J. R. (2001). Patriotism or opinion leadership?: The Nature and origins of the “Rally ‘Round the Flag” effect. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 45(5), 661-687. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022002701045005006

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77-101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Conway, B. A., Kenski, K., & Wang, D. (2015). The rise of Twitter in the political campaign: Searching for intermedia agenda-setting effects in the presidential primary. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 20(4), 363-380. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcc4.12124

Congressional Management Foundation. (2011). #SocialCongress: Perceptions and use of social media on Capitol Hill.http://www.congressfoundation.org/storage/documents/CMF_Pubs/cmf-social-congress-2011.pdf

Copenhaver, A., Schwendau, A., & Tewksbury, R. (2017). Southern legislative candidates’ expressions of support for criminal justice issues: The Internet and politics. Critical Issues in Justice and Politics, 10(1), 97-112. https://www.suu.edu/hss/polscj/journal/v10n1.pdf#page=99

Democratic National Committee. (2023). Preventing gun violence. https://democrats.org/where-we-stand/the-issues/preventing-gun-violence/

Entman, R. M. (1993). Framing: Toward clarification of a fractured paradigm. Journal of Communication, 43, 51-58. https://doi:10.1111/j.1460-2466.1993.tb01304.x

Executive Office of the President. (2022, June 23). Statement of administration policy: S. 2938–Bipartisan Safer Communities Act. https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/Bipartisan-Safer-Communities-Act-SAP-1.pdf

Gitlin, T. (1981). The whole world is watching: Mass media in the making & unmaking of the new left. University of California Press. https://www.ucpress.edu/book/9780520239326/the-whole-world-is-watching

Goffman, E. (1974). Frame analysis: An essay on the organization of experience. Harvard University Press.

Golbeck, J., Grimes, J. M., & Rogers, A. (2010). Twitter use by the US Congress. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 61(8), 1612-1621. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.21344

Guerin, B., & Innes, J. M. (1989). Cognitive tuning sets: Anticipating the consequences of communication. Current Psychology, 8(3), 234-249. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02686752

Hemphill, L., Culotta, A., & Heston, M. (2013). Framing in social media: How the US Congress uses twitter hashtags to frame political issues. Social Science Research Network. https://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2317335

Holody, K. J. (2020). Attributes in community and national news coverage of the Parkland mass shootings. In J. Mathews & E. Thorsen (Eds.), Media, journalism, and disaster communities (pp. 179-200). Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-33712-4_12

Hong, S., & Kim, S-H. (2016). Political polarization on Twitter: Implications for the use of social media in digital governments. Government Information Quarterly, 33(4), 777-782. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giq.2016.04.007

Iyengar, S. (1990). Framing responsibility for political issues: The case of poverty. Political Behavior, 12, 19-35. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00992330

Lee, J., & Xu, W. (2018). The more attacks, the more retweets: Trump’s and Clinton’s agenda setting on Twitter. Public Relations Review, 44(2), 201-213. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2017.10.002

Lee, J-K., Choi, J., Kim, C., & Kim, Y. (2014). Social media, network heterogeneity, and opinion polarization. Journal of Communication, 64(4), 702-722. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcom.12077

Nass, D. (2018, May 17). Parkland generated dramatically more news coverage than most mass shootings. https://www.thetrace.org/2018/05/parkland-media-coverage-analysis-mass-shooting/

Neuendorf, K. (2002). The content analysis guidebook. Sage. https://us.sagepub.com/en-us/nam/the-content-analysis-guidebook/book234078

Neuman, W. R., Guggenheim, L., Jang, S. M., & Bae, S. Y. (2014). The dynamics of public attention: Agenda-setting theory meets big data. Journal of Communication, 64, 193-214. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcom.12088

Osteen, O. (2022, August 11). Uvalde paper spotlights ABC News’ continuing coverage of local community in wake of massacre. ABC News. https://abcnews.go.com/US/uvalde-paper-spotlights-abc-news-continuing-coverage-local/story?id=88206090

Robinson, N. J. (2017, June 15). The politics of tragedy. Current Affairs. https://www.currentaffairs.org/2017/06/the-politics-of-tragedies

Schildkraut, J., & Muschert, G. W. (2014). Media salience and the framing of mass murder in schools: A comparison of the Columbine and Sandy Hook massacres. Homicide studies, 18(1), 23-43. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088767913511458

Shapiro, M. A., & Hemphill, L. (2016). Politicians and the policy agenda: Does use of Twitter by the U.S. Congress direct New York Times content? Policy & Internet, 9(1), 109-132. https://doi.org/10.1002/poi3.120

Silva, J. R. (2021). The news media’s framing of mass shootings: Gun access, mental illness, violent entertainment, and terrorism. Criminology, Criminal Justice, Law & Society, 21(2), 76-98. https://heinonline.org/HOL/LandingPage?handle=hein.journals/wescrim21&div=18&id=&page=

Straus, J. R. (2018). Social media adoption by members of Congress: Trends and Congressional considerations. Congressional Research Service. https://iadvocate.celiac.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/Social-Media-Adoption-by-Members-of-Congress-Trends-and-Congressional-Considerations.pdf

Straus, J. R., & Glassman, M. E. (2016). Social media in Congress: The impact of electronic media on member communications. Congressional Research Service. https://sgp.fas.org/crs/misc/R44509.pdf

Torres, A. (2018). Timeline: How the never again movement gained momentum after tragedy. WPLG 10. https://www.local10.com/news/parkland-school-shooting/timeline-of-never-again-movement-

Volsky, I., & Sakran, J. V. (2019). Unlike US, New Zealand isn’t just offering thoughts and prayers. CNN. https://www.cnn.com/2019/03/18/opinions/new-zealand-mosque-attack-us-gun-policy-volsky-sakran/index.html

Votesmart. (2023). National Rifle Association (NRA). Votesmart. https://justfacts.votesmart.org/interest-group/1034/national-rifle-association-nra

Wang, Y., Feng, Y., Hong, Z., Berger, R., & Luo, J. (2017). How polarized have we become? A multimodal classification of Trump followers and Clinton followers. In G. Ciampaglia, A. Mashhadi, & T. Yasseri (Eds.), Social Informatics, 440-456. Springer.

Wells, C., Shah, D. V., Pevehouse, J. C., Yang, J., Pelled, A., Boehm, F., Lukito, J., Ghosh, S., & Schmidt, J. L. (2016). How Trump drove coverage to the nomination: Hybrid media campaigning. Political Communication, 33, 669-676. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2016.1224416

Williams, N. W., Casas, A., Zuidema, W., Aslett, K., & Wilkerson, J. (2019). A social media approach to measuring frame impacts: What was the problem in Parkland? Policy Studies Journal, 50(1), 266-289. https://doi.org/10.1111/psj.12410

Zhang, Y., Wells, C., Wang, S., & Rohe, K. (2017). Attention and amplification in the hybrid media system: The composition and activity of Donald Trump’s Twitter following during the 2016 presidential election. New Media & Society, 20(9), 3161-3182. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444817744390

About the Authors

Allen Copenhaver, PhD is an Assistant Professor of criminal justice at Eastern Kentucky University. He conducts research on violent video games, intersections between law enforcement and those on the autism spectrum, and various other areas of research.

Nick Bowman, PhD (PhD, Michigan State University) is an Associate Professor in the S.I. Newhouse School of Public Communication at Syracuse University. His research examines the cognitive, emotional, social, and physical demands of interactive media, such as video games and social media.

Christopher J. Ferguson, PhD is a professor of psychology at Stetson University. He has researched the impact of various media on behavior for 20 years. He is a licensed psychologist and lives in Orlando with his wife and son.

CITATION (APA 7th Edition)

Copenhaver, A., Bowman, N., & Ferguson, C. J. (2023). Rage, prayers, and and partisanship: US congressional membership’s engagement of Twitter as a framing tool following the Parkland shooting. Journal of Mass Violence Research. https://doi.org/10.53076/JMVR74816