SHARE THIS ARTICLE

An Exploration of Female Mass Shooters

1Department of Sociology and Criminal Justice, William Patterson University

2Department of Criminal Justice, State University of New York at Oswego

https://doi.org/10.53076/JMVR95588 | Full Citation

Volume: 1, Issue: 1, Page(s): 62-71

Article History: Received June 22, 2021 | Accepted September 17, 2021 | Published Online October 4, 2021

ABSTRACT

This research note provides an exploratory examination of female mass shooters in the United States between 1979 and 2019. Specifically, this work provides descriptive statistics of perpetrator, motivation, and incident characteristics. Findings indicate female mass shooters more closely align with male mass shooters than general female homicide and mass murder offenders. The most valuable findings indicate female mass shooters are not motivated by relationship disputes, they often target the workplace, and they are more likely to work in dyads, especially when engaging in ideologically motivated attacks. A discussion of findings provides insight for mass shooting and gender scholars, as well as practitioners seeking to understand female involvement in mass shootings.

KEYWORDS

mass shootings, female homicide, gun violence

Mass shootings are an overwhelmingly male phenomenon (Peterson & Densley, 2019; Silva et al., 2021). In general, males account for the vast majority of homicide offenders and mass murderers (Fridel & Fox, 2019). Scholars attribute this to an evolutionary drive that pushes males to be more aggressive than females (Stone, 2015). Mass shooting studies often attribute these hypermasculine acts of violence to some form of male aggrieved entitlement or crisis of masculinity (Kalish & Kimmel, 2010; Kellner, 2008; Silva et al., 2021). In fact, Silva and colleagues (2021) find male mass shooters are often motivated by grievances with women. These gender-based mass shootings involve specific grievances with a woman connected to the shooter and/or general grievances with women or feminist ideology.

When women kill, during either single homicides or mass murders, the attacks often involve relationship disputes and/or familicides (Duwe, 2005; Fridel & Fox, 2019). In other words, it is rare for women to engage in gun violence targeting random individuals in a public setting. As a result, few studies focus on female mass shooters. However, these types of attacks do still happen, and recent high-profile incidents including the 2018 YouTube Headquarters shooting in California, the 2018 Rite Aid shooting in Maryland, and the 2019 JC Kosher Supermarket shooting in New Jersey, have increased public awareness and scholarly interest in female mass shooters (see for example: Jacobson, 2018; Park & Howard, 2019). As such, just as women have exhibited distinct trends and patterns in homicide offending (Fridel & Fox, 2019), it is important for research to also distinguish and understand female mass shooters.

This research note provides a preliminary and exploratory examination of female mass shooters in the United States between 1979 and 2019. Specifically, we provide descriptive statistics of the perpetrator, motivation, and incident characteristics. A discussion of findings highlight the common characteristics of female mass shooters and compares them with current knowledge of female homicide offenders and male mass shooters.

Literature Review

Given the rarity of female mass shooters, current research often involves case studies of a single female perpetrator (Fast, 2013; Katsavdakis et al., 2011; Sternadori, 2012). These case studies find shooting motivations include severe mental illness, shame, and a deteriorating life course (Fast, 2013; Katsavdakis et al., 2011). They also find female shooters intentionally plan and prepare for their attack and methodically attempt to kill as many individuals as possible before taking their own life (Katsavdakis et al., 2011). Despite these advancements in female mass shooter scholarship, individual case studies are unable to determine: (1) commonalities of female mass shooters, and/or (2) potential differences between male and female offenders. In terms of the latter, Lankford suggests, “We can’t really answer that question of differences between male and female offenders because we… don’t have enough female offenders for a statistically significant sample” (Adam Lankford in Park & Howard, 2019, para. 14). Nonetheless, there is a growing body of mass shooting research that can provide a framework for understanding the phenomenon at-large.

For instance, current mass shooting research finds perpetrators tend to be in their mid-30s, single/divorced, and often have a confirmed/suggested mental illness (Capellan & Gomez, 2018; Peterson & Densley, 2019). Perpetrators often have victim-specific motivations, followed by autogenic and ideologically based motivations (Capellan & Gomez, 2018;Osborne & Capellan, 2017). Typically, perpetrators carry out attacks in locations with personal or professional ties, and over half of incidents had a precipitating crisis event (Capellan & Gomez, 2018; Peterson & Densley, 2019). Attacks often conclude with the perpetrators arrest and suicide, and they are less commonly killed (Capellan & Gomez, 2018; Peterson & Densley, 2019). Taken together, these studies highlight the common characteristics that are worth considering in an examination of female mass shooters.

Methodology

In line with the commonly accepted definitions used in previous research (Peterson & Densley 2019; Schildkraut, 2018), we define a mass shooting as a gun violence incident, carried out by one or two perpetrators, in one or more public or populated locations, within a 24-hour period. Perpetrators must choose at least some of their victims at random or for their symbolic value (Newman et al., 2004; Schildkraut, 2018). We do not include felony-related (i.e., profit-driven criminal activity and gang violence) or familicide shootings (Krouse & Richardson, 2015; Peterson & Densley, 2019; Schildkraut, 2018). As is common in previous research (Capellan & Gomez, 2018; Schildkraut, 2018; Silva & Capellan, 2019), we include any shooters that attempted to incur four or more fatalities during the attack. This expansion of the victim-count criterion is done for two reasons. First, the four-death count criterion ignores random and systematic factors such as firearm malfunction and EMT responses (Capellan & Gomez, 2018). Second, this definition enables a larger population of female perpetrators, while still providing a targeted assessment of a specific gun-violence phenomenon.1

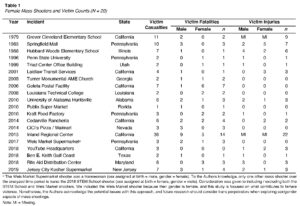

For data collection, we used open-source materials to identify all female mass shooters in the U.S. between 1979 and 2019.2 We primarily identified incidents using the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI, 2020) and New York Police Department (O’Neill et al., 2016) active shooter datasets. The collective FBI and NYPD reports included 18 female shooters. Additionally, two other perpetrators not captured in the FBI/NYPD datasets were identified: one in Stone (2015) and one in Schildkraut (2018).3 We then created comprehensive case files of open-source data for each incident by searching keywords in four search engines: Dogpile, Google, Nexis-Uni, and Newspapers. In the end, we identified 20 female mass shooters (see Table 1), and the case files were used to code the perpetrator, motivation, and incident variables. The operationalization of these variables is largely self-explanatory. For those requiring further detail, we provide descriptions of the variables in the results.

Analysis

This exploratory study provides previously unknown insight on female mass shooters. We follow previous rampage school shooting (Larkin, 2009; Madfis & Cohen, 2018) and mass shooting (Langman, 2020; Lankford & Silva, 2021) studies using a small sample / population of perpetrators to examine this rare form of violence. We provide descriptive statistics of the perpetrator, motivation, and incident variables that have been identified as important in larger examinations of the mass shooting phenomenon. We then compare these findings with previous knowledge of female homicide offenders and male mass shooters.

Results

As shown in Table 2, only one perpetrator was under 18-years-old (5%), and only one perpetrator was over 45-years-old (5%). Nearly half the perpetrators were 36-45 (45%), followed by 18-25 (25%) and 26-35 (20%). At the time of the shooting, most perpetrators were single or divorced (60%). With one exception, the rest of the perpetrators were in relationships and marriages that did not involve any issues attributing to the shooting. Three of the perpetrators (two married, one relationship) carried out attacks with their partner. Five of the women had children (25%), although three of them were no longer in a relationship with the father. Only one perpetrator stated a partner physically abused her in their lifetime (5%). Alternatively, three perpetrators stated they were sexually abused at some point in their lives (15%). Four perpetrators had a criminal history (20%), all of which involved either violence and/or threats of violence. Finally, the majority of perpetrators had a confirmed or suggested mental illness (65%), with the primary diagnosis being paranoid schizophrenia.

We considered the three mutually exclusive general attack motivations operationalized by Osborne and Capellan (2017), as well as more specific non-mutually exclusive motivations highlighted in previous research (Lankford, 2013; Silva & Greene-Colozzi, 2019b). In terms of the three general attack motivations, most perpetrators had autogenic motivations (50%); meaning they did not target any specific individuals, and their motivations were self-generated and attributed to their internal/psychological issues (Mullen, 2004). This aligns with the high rate of identified mental illness. Only three attacks (15%) were ideologically motivated (i.e., terrorism-related), and these extremist views were evenly distributed between the three major terrorism categories including: one jihadist-inspired attack, one far-right attack, and one far-left attack. The rest of the shooters had victim-specific motivations (35%); meaning they began by targeting individual(s) they knew, but eventually targeted other victims indiscriminately. When considering other, more specific motivations, the most common was problems at work (40%), including being suspended, fired, or otherwise disciplined. Four of the perpetrators were seeking to garner infamy and personal celebrity from the attack (20%). Only two incidents were rooted in family problems (10%) resulting in a family member being targeted. The Turner Monumental AME Church shooter targeted and killed her mother, and the Cedarville Rancheria Shooter targeted and killed her brother, niece, and nephew. Additionally, the Penn State University shooter was the only one motivated by a relationship problem. However, she did not target her significant other, and she instead targeted random individuals after their recent break-up.

Most attacks were not impulsive and involved a low to high level of planning (80%). Perpetrators with a high level of planning researched their target location, brought additional firearms / ammunition / other weapons, and/or had an array of protective / tactical gear (Osborne & Capellan, 2017). Of those with high levels of planning were the three incidents involving dyads (i.e., two perpetrators). These three dyad attacks also involved the three ideologically driven perpetrators. In line with the most common motivation, the primary attack location was the workplace (55%). The second most common location was schools (25%). However, a breakdown of the school attacks finds a diversion from popular conceptualizations of school shootings. Two attacks occurred in grade schools and three occurred in colleges. Four attacks (two elementary schools and two colleges) involved perpetrators who were not students and did not attack the school because of any school-related issues. The schools were just random locations to carry out their primarily autogenic and/or mental illness related motivations. The other college shooting (University of Alabama Huntsville) involved a Professor who did not receive tenure (i.e., workplace violence). One attack occurred in a religious institution (Turner Monumental AME Church), but the shooters motivation was not related to the shooting location. Four attacks occurred in open-space locations (i.e., shopping centers and restaurants) with which the perpetrator did not have any professional relationship. Finally, the most common conclusions to an attack involved the perpetrator being arrested (45%) and committing suicide (45%). Six of the nine perpetrators who committed suicide did so before the police even arrived. The least common conclusion was the perpetrator being killed (10%).

Discussion

As very few studies examine female mass shooters, this exploratory research fills an important gap in the literature. In general, this study identified a small population of female mass shooters (N = 20) over a 41-year time period. In other words, this work supports previous research finding female mass shooters are especially rare compared to male mass shooting and female homicide offenders (Fridel & Fox, 2019; Peterson & Densley, 2019). Nonetheless, through descriptive statistics, we offer a clearer picture of the women who carry out mass shootings, their motivations, and the circumstances of these events. Schildkraut suggests, “there are a lot more similarities than differences,” between male and female mass shooters (Jaclyn Schildkraut in Jacobson, 2018, para. 9). This research supports Schildkraut, for instance, finding female shooters are like their male counterparts in their age (i.e., average of 33 years old), mental health (i.e., commonly suggested/confirmed), level of planning (i.e., at least some), and attack conclusion (i.e., arrest and suicide > killed). Findings indicate male and female mass shooters are more closely aligned than female mass shooters and general female homicide offenders. For instance, like male mass shooters, female mass shooters are more likely to be single or divorced, and less likely to have a criminal history, constituting a departure from scholarly findings on female homicide offenders (Jurik & Winn, 1990; Pizarro et al., 2010). In general, three findings standout as providing the most interesting, previously unidentified, and valuable contributions to female mass shooting scholarship.

First, a relationship issue only motivated one shooter, and she did not target the male partner contributing to this grievance. This finding is distinct from general female homicide and mass murder offenders, who are often motivated by relationship disputes (Duwe, 2005; Fridel & Fox, 2019). Relatedly, only one female mass shooter indicated past domestic violence victimization, while research on female homicide offenders finds women often kill their intimate partners with whom they have had a history of domestic violence victimization (Jurik & Winn, 1990). This relationship dispute finding is also distinct from male mass shooters, with research finding one-third of male mass shooters are motivated by either a recent breakup/fight with their partner (i.e., a relationship-based precipitating crisis event), or problems with women at-large (i.e., the incel movement, lack of skills with women, virginity, etc.) (Silva et al., 2021; see also Farr, 2019; Osborne & Capellan, 2017). Similarly, while this research does not include familicides (i.e., a common motivation for female mass murder), it is still important to note these public female mass shooters never targeted their own children. Only two shooters involved family: one targeted their mother and the other targeted their brother, niece, and nephew.

Second, attacks predominately occurred within the workplace, and these attacks were often motivated by workplace problems. This presents a divergence from general female homicide and mass murder targets, and more closely aligns with male mass shooters. While the workplace is one of the most common locations for general mass shootings, more than half of female mass shooters targeted the workplace, surpassing previous findings indicating the workplace is the target in 28-36 percent of general mass shootings (Peterson & Densley, 2019; Silva & Capellan, 2019). Fridel (2021) suggests workplace attacks are often revenge-seeking and based on loose personal relationships. Indeed, our findings support this as workplace attacks often included retaliatory motivations connected to work-related issues. Some research suggests that women, more than men, have greater escalatory tendencies towards other women in the workplace (Winstok, 2006). However, this does not seem to be the case for female mass shooters, as there were more male victim fatalities and injuries than women (see Table 1). Future research should continue to explore the victim-offender relationships in female perpetrated workplace shootings, as well as across female perpetrated mass shootings in general.

Finally, this study finds a higher rate of female mass shooters (15%) work in dyads than general mass shooters (less than 1%) (Peterson & Densley, 2019). Interestingly, all these incidents involved a female working alongside a male counterpart. This aligns with general research finding females are substantially less driven to carry out mass shooting attacks, and these findings suggest that when they do, in some cases, this may be due to male coercion. This finding is particularly relevant to ideologically motivated mass shootings. This work finds all three ideologically motivated female mass shooting attacks involved male co-conspirators, who they were also in a relationship with at the time of the attack. Given ideologically motivated attacks often involve higher levels of planning (Capellan et al., 2019), it is not surprising that ideologically motivated female mass shooters have co-conspirators. Indeed, research suggests ideologically motivated male offenders are more likely to have co-conspirators than any other type of mass shooter motivation (Capellan et al., 2019). Yet, despite this similarity, there is a difference in the proportion of ideologically motivated dyads between men and women. When considering prior research on male mass shooters, approximately 8 percent of ideologically motivated shooters have multiple offenders (Capellan et al., 2019). This study, in contrast, indicates that multiple offenders carried out 100 percent of ideologically motivated attacks. This diverges from general terrorism research, which suggests husbands/boyfriends are rarely the driving force behind radicalized women (Scott, 2016). As such, research should examine the gendered nature of such ideological shootings to understand gendered pathways to ideologically motivated attacks and the dyad relationship.

Limitations

This is one of the first examinations of female mass shooters and there are limitations that should be considered in future research. First, this research only examines mass shooting incidents perpetrated by females in the United States; thus, neglecting this phenomenon as it may exist in other counties. Second, the reliance on open-source data may omit incidents of female perpetrated mass shootings, thereby undercounting the number of incidents that have occurred (Silva & Greene-Colozzi, 2019a). Third, this study included three dyads comprising of female mass shooters alongside male counterparts. Because of their cross-gender nature, it is difficult to parse out a motivation that is specific to the female partner. As such, research should consider exploring dyad relationships further, perhaps through case studies like those done on lone female perpetrators (Fast, 2013; Katsavdakis et al., 2011). Finally, this study is descriptive in nature and does not provide any inferential analysis related to female mass shooters. As an exploratory study, the use of descriptive statistics is appropriate; however, should future research consider hypothesis testing, appropriate comparative and/or inferential statistical methods should follow.

Implications

Despite relatively fewer cases of female perpetrators of homicide, scholars risk losing knowledge about female offenders when they are not uniquely considered (Fox & Fridel, 2019). This research finds female mass shooters in America tend to diverge from other female homicide offenders, particularly when considering relationship dispute motivations and workplace target selection. This is particularly important to consider for those providing guidance on preparedness and de-escalation of workplace conflicts. Women may not comprise a large proportion of mass shooters, but they are overrepresented in workplace mass shooting incidents. Indeed, more research is needed to assess these incidents, particularly the victim-offender relationship in such conflicts and the role gender might play in motivating these incidents.

Relationship grievances were not motivating factors for female mass shooters. Those scholars and practitioners wishing to understand gender and violence may consider this unique departure from female homicide offenders and male mass shooters in their future endeavors, such as theory development. These mass shootings do not stem from intimate partner violence as is often the case for female homicide offenders. Moreover, mass shootings perpetrated by females may not be a reaction to a perceived loss of femininity, as scholars find is the case for many male perpetrated shootings motivated by relationship grievances and their perceived loss of masculinity. Further theoretical development is needed to offer insight on female mass shooting motivations.

Finally, female mass shooters, though displaying many similarities with prior research on male mass shooters, are more likely to have co-conspirators, especially when ideologically motivated. Future research should continue to investigate these patterns and determine what makes female mass shooters unique. As research continues to examine female perpetrated mass violence, evidence-based policies and practices for prevention and response to these incidents should continue to develop. As suggested by this exploratory research, scholars and practitioners have much to gain from examining female mass shooters.

NOTES

- This definition somewhat aligns with the FBI and NYPD definitions of active shootings. There is debate over when to refer to an incident as a “mass” or “active” shooting (Freilich et al., 2020; Silva & Greene-Colozzi, 2019a). To create a unifying terminology, this study follows Freilich et al.’s (2020) suggestion that all incidents fitting this definition be referred to as a mass shooting.

- This study actually examines attacks in the aftermath of the 1966 Texas Sniper shooting – the “first” mass shooting in modern conceptualizations of the phenomenon (Peterson & Densley, 2019; Schildkraut, 2018). However, the data sources did not identify any female mass shooters between 1966 and 1978.

- The data collection process included a review of over 50 open-source collections of mass shootings (see Capellan & Gomez, 2018 for a comprehensive list of other sources reviewed). However, all the shooters were captured by those sources noted.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflicts of interest were reported by the authors.

REFERENCES

Capellan, J. A., & Gomez, S. P. (2018). Change and stability in offender, behaviors, and incident-level characteristics of mass public shootings in the United States, 1984–2015. Journal of Investigative Psychology of Offender Profiles, 15(1), 51–72. https://doi.org/10.1002/jip.1491

Capellan, J. A., Johnson, J., Porter, J. R., & Martin, C. (2019). Disaggregating mass public shootings: a comparative analysis of disgruntled employee, school, ideologically motivated, and rampage shooters. Journal of Forensic Sciences, 64(3), 814-823. https://doi.org/10.1111/1556-4029.13985

Duwe, G. (2005). A circle of distortion: The social construction of mass murder in the United States. Western Criminology Review, 6(1), 59-78. http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.486.4632&rep=rep1&type=pdf

Farr, K. (2019). Trouble with the other: The role of romantic rejection in rampage school shootings by adolescent males. Violence and Gender, 6(3), 147-153. https://doi.org/10.1089/vio.2018.0046

Fast, J. (2013). Unforgiven and alone: Brenda Spencer and secret shame. In N. Bockler, W. Heitmeyer, P. Sitzer, & T. Seeger (Eds), School Shootings: International Research, Case Studies, and Concepts for Prevention (pp. 245–264). Springer.

Federal Bureau of Investigation. (2020). Active shooter incidents 20-year review, 2000-2019. US Department of Justice. https://www.fbi.gov/file-repository/active-shooter-incidents-20-year-review-2000-2019-060121.pdf/view

Freilich, J. D., Chermak, S. M., & Klein, B. R. (2020). Investigating the applicability of situational crime prevention to the public mass violence context. Criminology & Public Policy, 19(1), 271–293. https://doi.org/10.1111/1745-9133.12480

Fridel, E. E. (2021). A multivariate comparison of family, felony, and public mass murders in the United States. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 36(3-4), 1092-1118. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260517739286

Fridel, E. E., & Fox, J. A. (2019). Gender differences in patterns and trends in US homicide, 1976–2017. Violence and Gender, 6(1), 27-36. https://doi.org/10.1089/vio.2019.0005

Jacobson, R. (2018, May 19). What female mass shooters reveal about male ones. Daily Beast. www.thedailybeast.com/what-female-mass-shooters-reveal-about-male-ones

Jurik, N. C., & Winn, R. (1990). Gender and homicide: A comparison of men and women who kill. Violence and Victims, 5(4), 227-242. https://doi.org/10.1891/0886-6708.5.4.227

Kalish, R., & Kimmel, M. (2010). Suicide by mass murder: Masculinity, aggrieved entitlement, and rampage school shootings. Health Sociology Review, 19(4), 451–464. https://doi.org/10.5172/hesr.2010.19.4.451

Katsavdakis, K. A., Meloy, J. R., & White, S. G. (2011). A female mass murder. Journal of Forensic Sciences, 56(3), 813-818. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1556-4029.2010.01692.x

Kellner, D. (2008). Guys and guns amok: Domestic terrorism and school shootings from the Oklahoma City Bombing to the Virginia Tech Massacre. Routledge.

Krouse, W. J., & Richardson, D. J. (2015). Mass murder with firearms: Incidents and victims, 1999–2013. Congressional Research Service. https://sgp.fas.org/crs/misc/R44126.pdf

Langman, P. (2020). Desperate identities: A bio‐psycho‐social analysis of perpetrators of mass violence. Criminology & Public Policy, 19(1), 61-84. https://doi.org/10.1111/1745-9133.12468

Lankford, A. (2013). A comparative analysis of suicide terrorists and rampage, workplace, and school shooters in the United States from 1990 to 2010. Homicide Studies, 17(3), 255-274. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088767912462033

Lankford, A., & Silva, J. R. (2021). The timing of opportunities to prevent mass shootings: A study of mental health contacts, work and school problems, and firearms acquisition. International Review of Psychiatry, 1-15. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540261.2021.1932440

Larkin, R. W. (2009). The Columbine legacy: Rampage shootings as political acts. American Behavioral Scientist, 52(9), 1309-1326. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764209332548

Madfis, E., & Cohen, J. W. (2018). Female involvement in school rampage plots. Violence and Gender, 5(2), 81-86. https://doi.org/10.1089/vio.2017.0027

Mullen, P. E. (2004). The autogenic (self‐generated) massacre. Behavioral Sciences & the Law, 22(3), 311-323. https://doi.org/10.1002/bsl.564

Newman, K. S., Fox, C., Roth, W., Mehta, J., & Harding, D. (2005). Rampage: The social roots of school shootings. Basic Books.

O’Neill, J. P., Miller, J. J., & Waters, J. R. (2016). Active shooter: Recommendations and analysis for risk mitigation. New York City Police Department. https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/nypd/downloads/pdf/counterterrorism/active-shooter-analysis2016.pdf

Osborne, J. R., & Capellan, J. A. (2017). Examining active shooter events through the rational choice perspective and crime script analysis. Security Journal, 30(3), 880-902. https://doi.org/10.1057/sj.2015.12

Park, M., & Howard, J. (2019, May 8). Why female shooters are rare. CNN. www.cnn.com/2019/05/08/health/female-shooters-rare/index.html

Peterson, J. K., & Densley, J. A. (2019). The Violence Project database of mass shootings in the United States, 1966–2019. The Violence Project. https://www.theviolenceproject.org/

Pizarro, J. M., DeJong, C., & McGarrell, E. F. (2010). An examination of the covariates of female homicide victimization and offending. Feminist Criminology, 5(1), 51-72. https://doi.org/10.1177/1557085109354044

Schildkraut, J. (2018). Mass shootings in America: Understanding the debates, causes, and responses. ABC-CLIO.

Scott, T. (2016). Female terrorists: A dangerous blind spot for the United States Government. University of Maryland Law Journal of Race, Religion, Gender, and Class, 16(2), 287-308. https://digitalcommons.law.umaryland.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi

Silva, J. R., & Capellan, J. A. (2019). A comparative analysis of media coverage of mass public shootings: Examining rampage, disgruntled employee, school, & lone-wolf terrorist shootings in the United States. Criminal Justice Policy Review, 30(9), 1312-1341. https://doi.org/10.1177/0887403418786556

Silva, J. R., Capellan, J. A., Schmuhl, M. A., & Mills, C. E. (2021). Gender-based mass shootings: An examination of attacks motivated by grievances against women. Violence Against Women, 27(12-13), 2163-2186. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801220981154

Silva, J. R., & Greene-Colozzi, E. A. (2019a). Deconstructing an epidemic: Determining the frequency of mass gun violence. In S. Daly (Ed.), Assessing and Averting the Prevalence of Mass Violence (pp. 39-67). IGI Global.

Silva, J. R., & Greene-Colozzi, E. A. (2019b). Fame-seeking mass shooters in America: Severity, characteristics, and media coverage. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 48(5), 24-35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2019.07.005

Sternadori, M. (2014). The witch and the warrior: Archetypal and framing analyses of the news coverage of two mass shootings. Feminist Media Studies, 14(2), 301-317. https://doi.org/10.1080/14680777.2012.739571

Stone, M. H. (2015). Mass murder, mental illness, and men. Violence and Gender, 2(1), 51-86. https://doi.org/10.1089/vio.2015.0006

Winstok, Z. (2006). Gender differences in the intention to react to aggressive action at home and in the workplace. Aggressive Behavior, 32(5), 433-441. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.20143

About the Authors

Jason R. Silva is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Sociology and Criminal Justice at William Paterson University. His research examines mass shootings, terrorism, and mass media. Silva’s recent publications have appeared in Aggression and Violent Behavior, American Journal of Criminal Justice, Justice Quarterly, International Journal of Comparative and Applied Criminal Justice, and Victims & Offenders.

Margaret A. Schmuhl is an Assistant Professor of Criminal Justice at The State University of New York at Oswego. Her research focuses on critical explanations of violence against women and punishment.

CITATION (APA 7th Edition)

Silva, J. R., & Schmuhl, M. A. (2021). An exploration of female mass shooters. Journal of Mass Violence Research, 1(1), 62-71. https://doi.org/10.53076/JMVR95588